Seven years ago, Milagros Genao weighed 235 pounds. Her blood sugar level, or A1C, soared at 11.8%—nearly double the threshold for diabetes. These numbers put her at high risk for serious diabetes complications, from heart attack to stroke to kidney failure.

“I felt so depressed,” Milagros says. “I was in denial, not accepting my diabetes.”

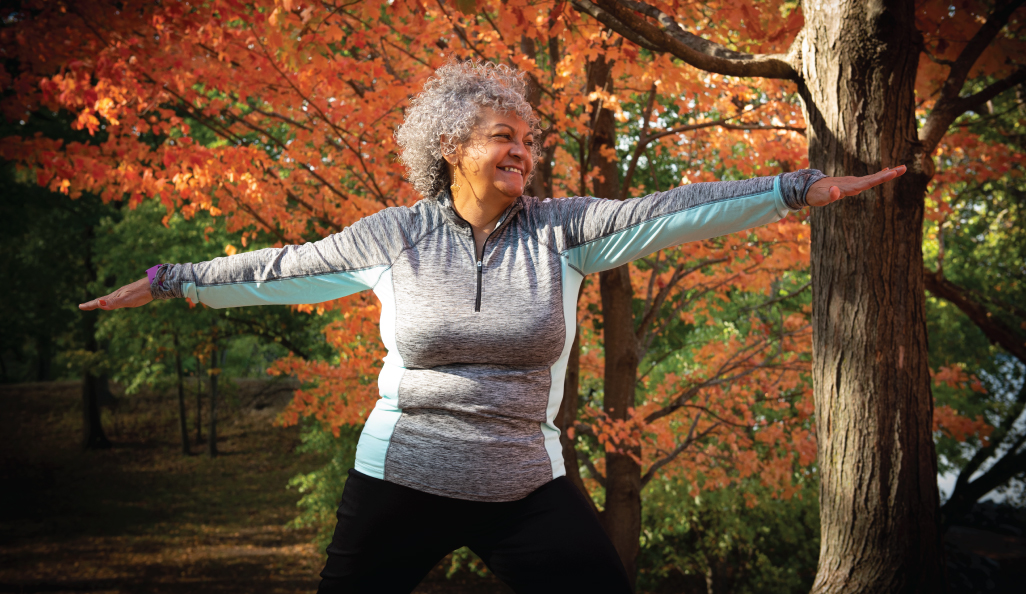

Then she found Comunidad en Acción (Community in Action, or CEA), a program for Spanish-speaking patients with diabetes and pre-diabetes. Milagros spent three hours every Thursday exercising and learning about nutrition at the Southern Jamaica Plain Health Center, a primary care site of Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She got so hooked on CEA’s yoga and Zumba dance classes, she became a regular at the center’s other group classes throughout the week.

Once Milagros started changing her diet, including cutting sugar from her daily coffee and removing starchy foods like white rice, she shed 30 pounds and began transforming her health. She also became a trusted friend and mentor to other CEA participants.

In March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic struck Boston, CEA suspended in-person group meetings, along with countless area services and organizations. While it stung to lose access to the classes and camaraderie of caregivers and friends, Milagros knew the closure would help protect vulnerable patients like her from the coronavirus. Hunkered down at home, she held onto the lessons she learned to keep forging ahead.

A SICK NATION GETS SICKER

Milagros is one of the more than 107 million adults in the U.S. who are considered obese. The national obesity rate for adults sits above 42%, compared with 18% three decades ago.

As obesity rates rose, so did rates of chronic diseases including diabetes, stroke, cancer, and kidney disease, which kill more than 1 million people each year. Looking at the prevalence, statistics reveal that six in 10 adults in the U.S. have at least one chronic disease and four in 10 have more than one. This epidemic endangers Americans’ lives and increases vulnerability to the latest health threat, COVID-19.

“The COVID-19 pandemic exposes our collective poor health as a country,” says Marie McDonnell, MD, director of the Brigham Diabetes Program. “We’ve seen that underlying health conditions may weaken or compromise the immune system, causing higher risk for severe complications from COVID-19.”

A RIDDLE WITH STRAIGHTFORWARD SOLUTIONS

While genetics plays a role for some people with chronic disease, healthy behaviors can mitigate and even prevent many of these conditions, as Milagros learned. Studies led by Brigham researchers and others worldwide show that taking simple steps—eating nutritious foods and getting regular exercise—are most effective in preventing or treating chronic illnesses.

For example, the National Institutes of Health found that losing as little as 5% to 7% of body weight is more effective than medication in preventing or delaying type 2 diabetes. In the late 1990s, a clinical trial called the Diabetes Prevention Program divided participants into three groups. After three years, participants randomly assigned to the lifestyle change group achieved modest weight loss and lowered their chances of developing type 2 diabetes by up to 58% compared with the placebo group.

Meanwhile, the group assigned to take the drug metformin experienced less success. They decreased their chances of developing type 2 diabetes by 31% compared with the placebo group. An ongoing study continues to show how healthy habits or medication can successfully prevent and delay diabetes. The results are so astounding, the CDC launched a national program to share these findings with more Americans.

“Preventing diabetes has a huge impact on quality of life as well as how long patients will live,” says McDonnell. “The best tools are in our refrigerators and our sneakers.”

Once McDonnell’s team diagnoses a patient with diabetes, it recommends healthier eating and 150 minutes of exercise each week. Knowing the challenges of changing long-standing habits and behaviors, her team encourages at least one or two visits with a nutrition specialist to ease patients into a new mindset.

NEW HABITS, STEP BY STEP

A few years ago, when her daughter left Boston to attend college, Luz Vargas steadily ate comfort foods to fill the void of her absence.

“I used to run into the grocery store, buy a pint of ice cream, and eat it all at once,” she says.

Luz’s primary care doctor at the Brigham noticed her weight gain. When the 56-year-old’s A1C test confirmed a diabetes diagnosis, Luz immediately made an appointment with one of the Brigham’s diabetes clinics, followed by visits with a nutritionist.

Little by little, Luz began eating healthier foods, replacing tortillas and rice with eggs, peppers, and other nutrient-rich foods. She also turned to two friends with diabetes, and they began sharing healthy recipes and walking together.

In two years, she dropped from 199 pounds to 140. When the COVID-19 pandemic kept her isolated from her exercise companions and regular routine, she gained 10 pounds in three months. But with the tools learned in the diabetes clinic, Luz quickly recognized this backslide and got back on course with healthy habits.

“With the stress of the pandemic, I wanted to eat everything,” Luz says. “I realized by eating these bad foods, I’m not treating myself―I’m killing myself.”

GAINING CONTROL AMIDST STRESS

When Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker issued a stay-at-home advisory in March to slow the spread of COVID-19, panicked grocery shoppers stocked up on nonperishable foods, including snacks and comfort foods.

Meanwhile, staff in the Brigham’s Department of Nutrition began coaching patients through eating challenges intensified by the pandemic. The department’s director, Kathy McManus, MS, RD, LDN, says common trouble spots included stress eating and disrupted routines. The nutritionists, who switched to virtual care in March, have been emphasizing foods that can help boost immune health, from berries and dark leafy greens to turmeric and oregano. And their advice goes beyond food.

The nutrition team guides patients along the path to new health habits using information grounded in cognitive behavioral science.

“We encourage patients to set a couple of realistic goals at a time and post them where they can see them, like their fridge or bathroom mirror,” Bradshaw says. “Patients who achieve bigger results show up for appointments, use a self-monitoring tool like a food log, and plan meals and activity for the week. Success comes with modifying your behavior and being consistent. It’s about taking baby steps and building confidence, especially in times of uncertainty and stress.”

This all takes time, Bradshaw says. Rather than a period of weeks or months, the team looks at a year or two years to see true patterns of change.

STAYING FOCUSED

Years ago, Liz Peet tried commercial dieting plans with little success. In 2018, the 57-year-old signed up for the Brigham’s Program for Weight Management, hoping the medically supervised program would bring different results.

“My back was hurting,” says Liz, who had a spinal infection years earlier. “Walking was hard. Sleeping was hard. Sitting was hard. I looked in the mirror and said, ‘Hey, you’re pretty heavy and have a tricky spine. Stop straining your back with extra weight. It’s time to focus on losing weight.’”

“I enjoy cooking and thinking about recipes each week,” Liz says. “At the grocery store, especially lately with one-way aisles, it can be tempting walking by snacks. I say to myself, ‘I’m not paying attention to the bags of chips. I’m happy with carrots.’”

Liz lost 75 pounds through the program. Her ability to move without pain is her most satisfying reward and motivates her continued healthy routine, including long daily walks. Weekly program meetings, which went virtual during the pandemic, also give her fuel.

“By sharing challenges and successes with my group, I don’t feel like I’m sitting in my apartment all alone,” she says. “It’s helpful hearing some people are struggling, too, and that others have found productive, positive ways to handle things.”

The rest of the week, Liz is on her own to make choices.

“I have to put in the work,” she says. “I’ve been building one healthy habit at a time and layering it on top of another. Now, it’s a constellation of healthy habits.”

FOLLOWING THE TRAIL OF EVIDENCE

McManus and her staff use the latest evidence to educate their patients. One study by Harvard researchers in early 2020 found that those who follow five healthy habits can live up to a decade more without developing certain chronic diseases.

When the nutritionists see new patients, they assess current eating habits and suggest cutting back some foods and adding others. They discuss various diets, including the Standard American Diet (SAD), which is low in vital nutrients and high in sugar, refined carbohydrates, and saturated fat. By comparison, the Mediterranean diet emphasizes foods with high nutritional content, and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet focuses on lowering sodium and increasing nutrients to reduce blood pressure.

“The Brigham was a primary site for the DASH clinical trial in the late 1990s,” McManus says. “The eight-week study showed that people with hypertension could significantly lower their blood pressures in a short period with the DASH diet. They started to see results within two weeks.”

With various studies to guide them, McManus and her team tailor recommendations for each patient. The team also urges patients to be realistic about developing new habits.

“I like the 80/20 rule for people trying to establish new behaviors,” McManus says. “So, 80% of the time, they’re pretty on target with goals and 20% of the time, they’re choosing some of their favorite foods, to be enjoyed and savored. We help figure out the frequency and amount.”

TOOLS TO PERSEVERE

Primary care physician Lilliana Rosselli-Risal, MD, founder of Comunidad en Acción, knows the difference food makes in confronting obesity and diabetes.

“If you take medication and keep eating sugar, that won’t solve the underlying problem with diabetes,” Rosselli-Risal says. “You need to eliminate what’s making you sick. I believe the body has the power to heal itself through nutrition.”

Based on evidence from studies like the Diabetes Prevention Program, Rosselli-Risal designed CEA to teach patients like Milagros the importance of lifestyle changes. Staff members including a diabetic nurse educator, social worker, and case manager collaborate with Rosselli-Risal to offer patients information.

Back in February, prior to the COVID-19-induced shutdown, Milagros joined one of CEA’s weekly meetings. Easy banter and laughter filled the hallway as participants greeted each other with hugs and kisses. Milagros headed to the kitchen to prepare salad while other members took turns weighing in on the scale.

At lunchtime, Milagros shared her gratitude with the group. The 62-year-old said, “Coming here showed me I needed to change. My health and mood have improved so much.”

Although the program closed its doors in response to the pandemic, the group’s camaraderie remains strong. Milagros still calls nearly all 30 participants each week to check on them and stay connected.

“They’re such a cohesive group and took it upon themselves to take care of each other,” says diabetic nurse educator Maureen Balaguera, RN, CDE, CNL. “It’s beautiful.”

As Milagros adjusted to life at home, her commitment to her health did not waver. With knowledge from CEA, she stuck with her nutrition regimen. She also started online Zumba and yoga classes offered by instructors from the center.

EMBRACING THE JOURNEY

From the stress of the pandemic to the lure of old habits, any number of barriers could have stopped Milagros, Luz, and Liz in their tracks. But they each moved ahead with the support of their buddy systems and newfound knowledge. These women see their health transformations as an ongoing path of self-care and improvement attainable even amid a pandemic, precisely what McManus hopes for patients.

“This isn’t a destination; it’s a journey of embracing changes over the long term,” McManus says. “Lapses will happen. It doesn’t mean what someone is doing isn’t working or they’re a failure. It’s just a lapse. So, we pick ourselves up and keep going. This is a life-changing journey.”