Every March on Match Day, thousands of medical students eagerly anticipate learning which residency training program they will match into across the U.S. In 2021, the day marked a new chapter at Brigham and Women’s Hospital as the community celebrated the most racially diverse group of incoming residents in the Brigham’s history.

“Match Day felt like Christmas to me,” says Valerie Stone, MD, the Department of Medicine’s vice chair for diversity, equity, and inclusion. “I kept staring at the list as though it must be a mistake. Too amazing to be true.”

Across all of the hospital’s residency programs, 27% of the 2021-2022 interns are historically underrepresented in medicine (URiM), nearly triple the year before. In the Brigham’s largest training program—the internal medicine residency—the number nearly doubled.

For Samantha Cothias, MD, RN, BSN, matching into the internal medicine residency is a dream realized. As a teenager, she moved to Massachusetts from Haiti and began volunteering at the Brigham. Hoping to become a doctor, Cothias started her career as a patient care assistant and then a nurse at the hospital. As she approached graduation from medical school and applied to residency programs, she ranked the Brigham as her top choice.

“On Match Day,” says Cothias, “I felt ‘little me’ was looking up and saying, ‘You’ve made it! You can only go up from here!’”

Building momentum

Hospital leaders see new possibilities for the future—if they keep building on this success.

“We recognize the system is inherently racist and based on privilege—not just the medical system but the society we live in,” says Joel Katz, MD, vice chair for education in the Department of Medicine and director of the internal medicine residency. “We have the opportunity to train better doctors and innovative leaders in healthcare who will help us make the world a better, safer, and healthier place for patients, especially groups that are underrepresented.”

Katz, Stone, and their colleagues—in concert with residents—are looking at the internal medicine training program through an equity lens. They’re asking deep questions about how to improve existing practices, from recruitment to the training curriculum to patient care. They want to educate new generations of physicians who are better prepared to care for an increasingly diverse nation.

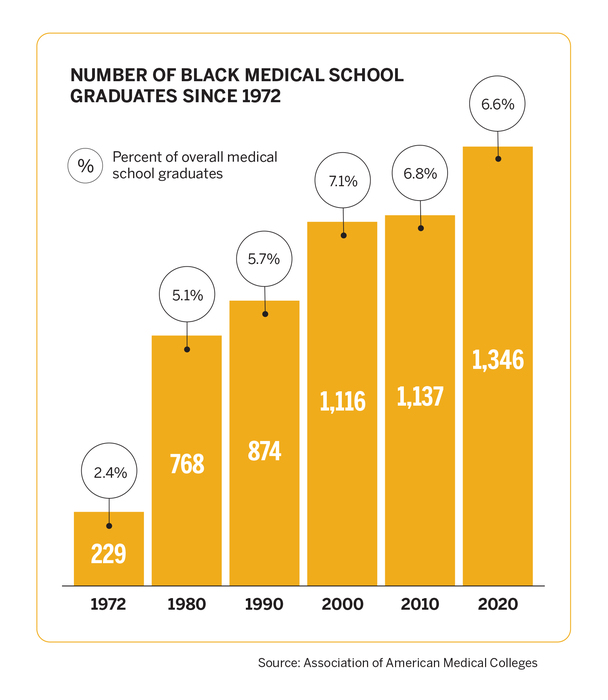

Numerous research studies by organizations including the National Academy of Medicine and the World Health Organization show that increasing diversity among healthcare workers improves patient care and reduces health disparities. But the current U.S. physician workforce does not represent the diversity of the overall population. In fact, there are large inequities.

The most recent report of all actively practicing physicians nationwide identified 5.8% as Hispanic/Latinx, 5% as Black or African American, and .3% as American Indian or Alaska Native, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. That same year, data from the U.S. Census showed 18.3% of the population as Hispanic/Latinx, 12.7% Black or African American, and .9% American Indian or Alaska Native.

“Ideally, our staff will reflect the diverse backgrounds of our patients,” says Stone. “When there’s a more diverse workforce, it informs the way all of us care for patients from different cultures.”

Rethinking a system built on inequity

Medical training programs have long used similar tactics when it comes to recruitment—including consulting established networks of contacts for recommendations and emphasizing test scores. This system favors applicants with societal advantages. Rebuilding it demands new ways of thinking.

When Evan Michael Shannon, MD, now an assistant professor at UCLA, started as a resident at the Brigham in 2015, he was surprised to be the only Black man in his intern class. Although 15% of the nearly 200 residents in the program were from underrepresented groups, they were mostly Latinx, he explains.

In his second year, he established a Diversity and Inclusion Committee to create a structure of affinity and activism for his peers. After working with faculty to boost recruitment, they saw a slight rise in diversity. When the department hired Stone for a new position dedicated to recruitment and retention, it set the stage for more dramatic change.

“Dr. Stone has been a real powerhouse,” says Shannon, a chief resident last year. “Having a person of her seniority, a Black woman rising up the ranks through Harvard Medical School as a full professor, turbocharged the work.”

To develop a new approach, Stone called on Shannon, Katz, and other faculty to join her in reviewing and rebuilding the residency recruitment process.

One big shift included more holistic reviews of all applicants. Rather than disproportionately valuing criteria such as test scores, they looked comprehensively at each candidate’s experiences and skills with equal weight.

But unconscious biases can cloud decisions. So, instead of encouraging the 60-plus faculty and resident evaluators to take unconscious bias training, they required it.

Every year, there are more qualified applicants than interview slots. To look closely at all URiM applicants who met residency criteria, they committed to more interviews. The committees that screened, interviewed, and selected applicants had greater gender and racial diversity than any year prior.

Members of the residents’ Diversity and Inclusion Committee also built up a social media presence using the residency’s Twitter account, @BrighamMedRes, and creating a new account, @BrighamD, where they highlighted the growing diversity of the residency program and faculty and promoted work on health equity.

Of the 78 interns who joined the Brigham’s three-year internal medicine residency for 2021-2022, 23, or 29.5%, identify as Black or Latinx. The year before, 15% of the intern class included individuals from underrepresented groups.

Reflecting on the outcome, Katz says, “We’re thrilled by the diverse backgrounds of these talented physicians and their potential as local and national healthcare leaders.”

Creating a more inclusive environment

Recruiting the most diverse intern class ever is a starting point, notes Stone.

“Doctors who are underrepresented in medicine have a greater burden to move along the path,” she explains.

At the Brigham, and academic medical institutions nationwide, diversity decreases as physicians move along the career path. At each transition point between medical school, residency, fellowship, and faculty, the number of underrepresented physicians drops further.

“Building the pipeline of diverse academic physicians is critical,” says Katz. “We need to better understand and eliminate the barriers that discourage underrepresented physicians from staying.”

Stone adds, “It’s crucial that we offer this amazing class of interns mentoring and community-building opportunities to create a culture of inclusion.”

After the historic Match Day in 2021, Stone began developing and strengthening the mentoring program for URiM residents—hiring 2021 residency graduate Zainab Jaji, MD, to oversee the work.

“Half our interns who are URiM this year are Black,” Stone says. “This is where it starts. If we can retain a good proportion of these residents, this is how we build a more diverse faculty. Everything we do makes a difference.”

Preparing residents to create a healthier and more just world

The end goal of the Brigham’s internal medicine residency program is to train residents to be exceptional clinicians and leaders. Residents participate in clinical training, research, and career mentoring, and take on teaching and leadership roles. In addition, they study, prepare presentations, and attend community-building activities.

An important element of their learning and advocacy comes through the residency’s commitment to health equity and social justice. In the spring of 2020, residents responded with urgency as two national crises unfolded: the COVID-19 pandemic and an intensifying movement for racial justice.

“The killing of George Floyd was an inflection point for us all,” says Katz, “where injustices became more public and apparent.”

That June, residents and faculty held multiple brainstorming meetings and developed more than 70 ideas to address racism in medicine.

One of their action items was to integrate more teaching on racism in the curriculum. They encouraged more open and direct dialogue during daily patient rounds and teaching conferences that take place eight to 10 times per week. Now, discussing health equity when presenting a patient case is a natural part of their work.

This has created a profound impact, says Duaa AbdelHameid, MD, a resident who is completing an external training program and scheduled to return in 2023 as a senior resident. “Racism in medicine is something we know exists but nobody talked about outright when I was an intern. Last year, everyone from the top down talking about these things significantly changed the culture. It warms my heart and gives me so much hope for how things will be if it continues this way.”

Last year while a chief resident, Shannon thought of another way to infuse teaching on racism. His inspiration: the 1619 podcast, an audio series produced by The New York Times. In small groups, residents discussed “How the Bad Blood Started,” which chronicled how Black Americans were refused access to medical care for decades.

“We held interns’ pagers to make sure they could participate without interruption,” says AbdelHameid. “In medical education, our schedules are so full, but Joel Katz and the leadership have done a phenomenal job carving out time for learning about racism and equity like any other subject. It’s integral to our education as doctors in America and learning how to care for patients.”

These additions to the curriculum build on prior changes made by residents and faculty, explains Maria Yialamas, MD, an associate director of the residency. In the years immediately leading up to 2020, she says, the residency developed a microaggression response training and an elective Leadership for Health Equity Pathway.

“Residents have led the charge in this work,” Yialamas says. “They challenge the residency, the Department of Medicine, and the hospital to do even better.”

Revealing inequities through research

Brigham residents have also helped flag inequities in care. As newcomers to the medical profession, they bring fresh perspectives and questions to long-standing practices.

In 2015, some residents observed inconsistencies in care for patients of color experiencing heart failure. To investigate, they teamed up with staff to examine 10 years of records from nearly 2,000 patients treated for heart failure at the Brigham. Their research showed patients of color were more likely to be transferred to the general medical service, and white patients, especially men, were more likely to go to the cardiology unit, where they received more specialized care with better health outcomes. The reasons for this were complex, including structural inequities that disadvantage patients of color nationwide. This work raised awareness and sparked collaboration across departments to improve care.

“The heart failure study continues to be an important learning tool for all of us,” says Yialamas. “When we are caring for patients with heart failure in the hospital, we now pause and discuss whether there should be a cardiology consult.”

In June 2020, the residency brainstorming meetings inspired a new research project. Resident Yannis Valtis, MD, formed a working group with three other residents to examine the question, “Are care providers calling security response more often for Black patients than white patients?”

Led by Shannon as their primary faculty advisor, the residents collaborated with security, nursing, and psychiatry. “Everyone we talked to across the Brigham was eager to talk and share data, and wanted to know the answers, too,” says Valtis.

Working with the hospital’s analytics, reporting, and insights team, they reviewed data on 24,212 patients discharged from inpatient units and concluded that medical teams were almost twice as likely to call security for Black patients compared with white patients. Of the patients in the study, 10% identified as Black, 7% as Latinx, and 76% as white.

Last fall, Valtis presented the data at a residency conference and asked more residents to join phase two of the project: implementing an intervention to change current practices. One potential next step, he says, is to provide de-escalation training for caregivers.

Valtis invited emergency medicine physician Farah Dadabhoy, MD, to provide practical tips in managing agitated patients. As an emergency medicine resident last year, Dadabhoy developed a training on unbiased de-escalation now required for all caregivers in the Emergency Department.

Is structural racism affecting this patient’s care?

Residents Miriam Kwarteng-Siaw, MD, and Kelly Schuering, MD, are addressing another long-standing inequity: systemic differences in care for patients with sickle cell disease. An inherited blood disorder, the disease causes debilitating pain, damages multiple organs, and shortens life expectancy.

“Some patients are hospitalized once every year or two for a pain crisis, and others are in the hospital almost monthly,” Kwarteng-Siaw says.

Patients with sickle cell disease were being admitted to multiple medicine teams over several floors in the Brigham’s two patient towers. This fragmented and delayed patients’ care and disrupted residents’ experience in caring for this population.

“In the U.S., patients with the disease are mostly of African American descent,” says Kwarteng-Siaw. “There seemed to be racial injustice going on, even if unintentional.”

Kwarteng-Siaw, Schuering, and other residents approached general medicine and hematology leaders—who were also eager to improve the patient experience. They persisted through competing priorities, including complications of restructuring units for patients with COVID-19.

Residents encountered another hurdle: Patients with sickle cell disease need high levels of opioids but bias and knowledge gaps among caregivers can hamper care.

“Some patients express that clinicians aren’t comfortable with the amount of pain medications they need,” says Kwarteng-Siaw. “And some clinicians don’t believe how much pain patients are having.”

A co-leader of the residency’s Racial Justice and Health Equity Committee, Schuering presented on bias in pain management and sickle cell disease last summer as part of the residents’ conferences. She discussed research on racial disparities in pain management and the effects of stigma on patients, along with two case studies. A patient also joined via video from her hospital room to share her experiences.

Last September, the Brigham’s leadership launched a new approach with dedicated teams of residents caring for patients with sickle cell disease and increased education for physicians and nurses.

“To solve these inequities, we need to push forward both systems-level change and education,” Schuering says. “The process feels hard and frustrating, but we’re making progress.”

To encourage more initiatives like this, the Department of Medicine established a Health Equity Innovation Program in 2019 to offer grants for projects aiming to improve health equity. So far, the department has provided nearly $1.5 million in grants for 27 projects, including new approaches for heart failure patients and examining inequities in cancer care.

Opening up the conversation

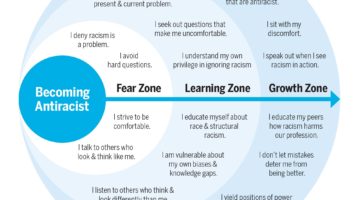

To continue reducing inequities, Stone says, the healthcare workforce needs opportunities to learn about and discuss racism.

Last year, Stone enlisted the help of the hospital’s Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion to create an antiracism training, which was delivered to 425 Department of Medicine faculty over two 3-hour virtual sessions. Residents completed a 3-hour version at their class retreats. Brigham facilitators led small breakout groups to create a safe space to share thoughts.

“We wanted everyone to get more comfortable talking about race and racism,” says Normella Walker, director of the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. “One of the big concepts we discussed was racial framing—which describes how people of color and white people tend to have different perspectives and approaches when talking about racism and how it manifests.”

To better grasp the impact of racism, they talked about topics including the history of race in medicine, types of racism, and how white dominant culture affects organizational environments.

“By being aware of racism, we can make change,” Walker says. “We have decision points every day where we can choose to lean in.”

Providing this experience for residents was especially satisfying for Walker.

“Antiracism training will make residents better practitioners and colleagues and create a better work environment,” she says. “The world is much more diverse than for previous generations of physicians. Trainees need to develop cultural humility to practice good medicine.”

Changing the culture of medicine

To keep the conversation going, Stone coordinated with Walker and her team to offer book groups related to racism. By the end of 2021, more than 700 faculty participated in antiracism training or a book discussion.

“The goal is to change the culture and create a shared understanding by providing education,” Stone says. “I want people to recognize that the experience of Black and Latinx faculty is different. We need to create a more inclusive environment where all employees feel valued and celebrated.”

Developing a new paradigm takes innovation, persistence, and momentum.

“The pace of change has accelerated,” says Stone. “I’m proud of what we’ve achieved so far. We’re making progress on a long journey.”