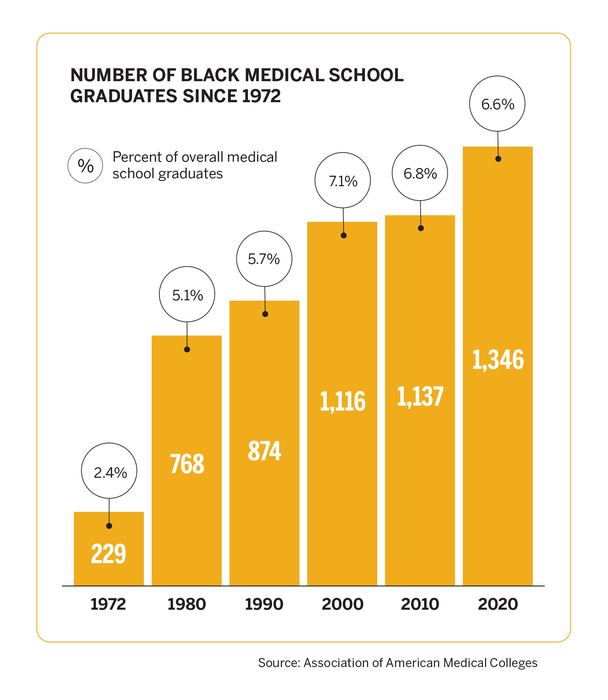

Every physician in training today is part of a system steeped in historical inequities. When the nation’s first medical schools were established, they accepted white men exclusively. In the late 1800s, Black medical schools began opening.

Around that time, the American Medical Association (AMA) decided many medical schools were providing an inadequate education and established national standards.

These requirements—outlined in the Flexner Report of 1910—proved too costly for many schools. Half of all U.S. medical schools, including five of the seven Black medical schools, closed.

Access to medical education remained limited for people of color, as was membership in medical professional societies. After the Civil Rights Act passed in the 1960s, historically white medical schools and hospitals began to integrate, AMA chapters opened membership to Black physicians, and segregated care in hospitals became illegal.

Despite these changes, history’s effects linger. In 2021, the AMA published an article estimating that the Flexner Report resulted in 30,000 to 35,000 fewer Black physicians joining the workforce since 1910.

Inequities in medical education also hindered the development of physicians from Latinx, Native American, and other underrepresented backgrounds. This has created an uneven path for many in the medical field.