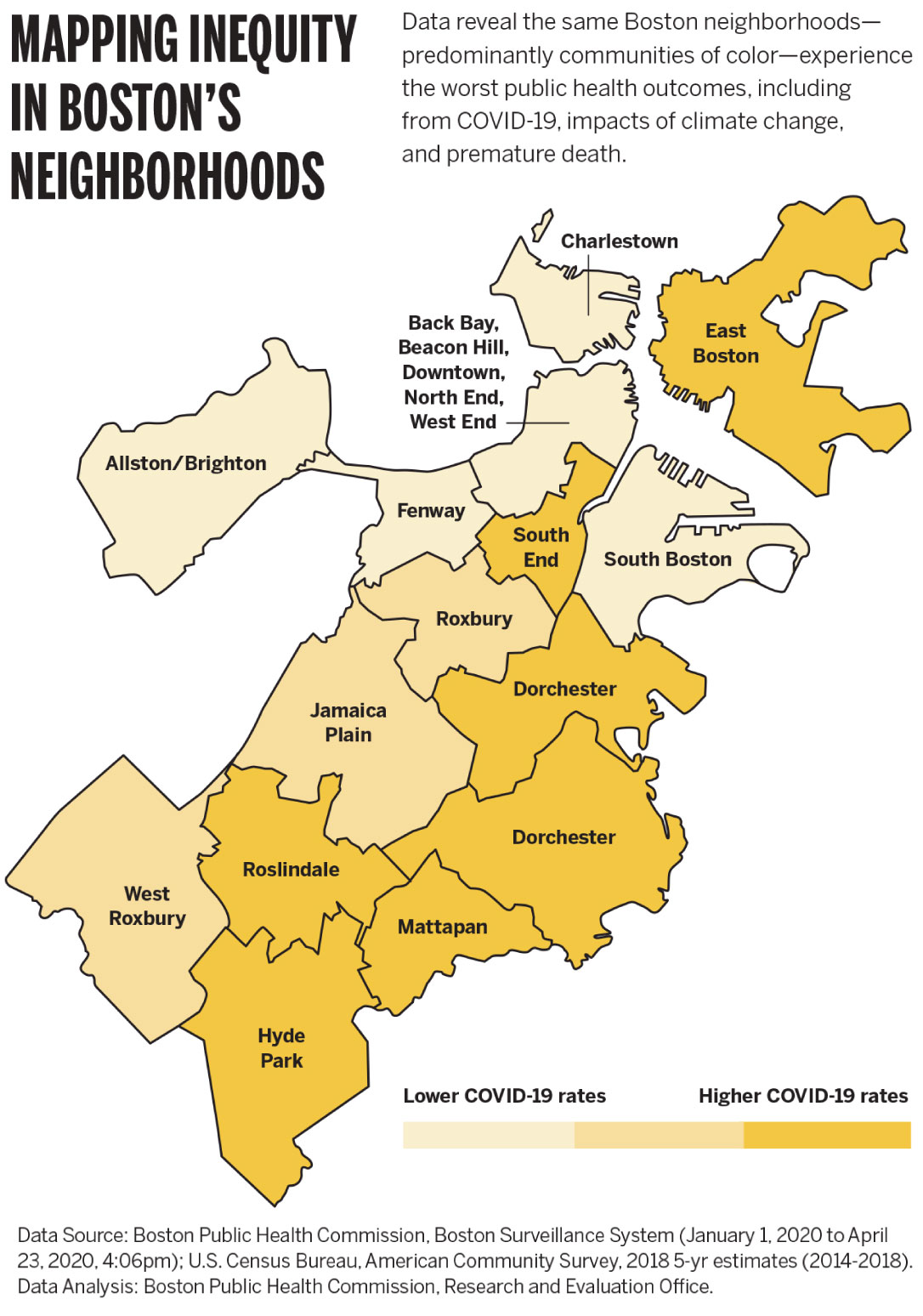

Throughout the United States, deep and long-standing health inequities exist along socioeconomic and racial lines. In Boston, Back Bay residents enjoy the city’s highest life expectancy at almost 92 years. A few zip codes away, Roxbury residents’ life expectancy is just 59 years, the city’s shortest. Wedged between these neighborhoods is Brigham and Women’s Hospital, serving patients and employing staff who live worlds apart. What explains a more than 30-year difference in life expectancy between residents who live four miles apart, in the shadows of several world-renowned healthcare institutions?

The wealth-health gap

Decades of research show that access to medical care accounts for around 20% of what makes a person healthy. The remaining 80% of our health is driven by the myriad ways our well-being and lifespans are dictated by what are called social determinants of health: reliable access to safe and affordable housing, quality education and work opportunities, nutritious food, recreation, clean air and water, and other factors unevenly available throughout the nation.Leaders at the Brigham and its parent organization, Mass General Brigham (MGB), are working harder than ever to tackle social determinants of health and close health gaps in Boston and beyond. They are reaching people directly in their neighborhoods, understanding the circumstances that can restrict health choices, striving to eliminate those barriers, and redesigning healthcare for a more equitable future.

Tom Sequist, MD, MPH, is an internist at the Brigham and the chief medical officer for MGB. Sequist is familiar with the public health consequences of long-term disinvestment in neighborhoods where Black, Brown, and immigrant families live: fewer opportunities, more adverse life experiences, more toxic stress that prematurely weathers the body. All of these fuel higher rates of chronic disease and early death.

“For decades, government-sponsored policies intentionally prevented Black and low-income residents from establishing and growing wealth through homeownership,” he explains. “That legacy is still felt today with wealth-earning potential relatively stagnant in these communities. And wealth buys the flexibility, resources, and insulation from the worst effects of a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Sequist is building coalitions across the Brigham, as well as MGB, to ensure all patients can access top-notch care. He and his colleague, Elsie Taveras, MD, MPH, are spearheading the United Against Racism initiative, a system-wide roadmap for the Brigham and its peer institutions to become antiracist organizations, with specific timelines and metrics of success.

“COVID-19 exposed the profound gaps in health that have existed for a long time,” says Taveras, chief community health equity officer for MGB. “We’re thinking carefully about the context in which racism and inequities exist and lead to racial inequities and suboptimal outcomes for our BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] patients.”

United Against Racism has ambitious goals for community health, including focusing on social determinants of health across all primary care sites and boosting resources to vulnerable neighborhoods. The program also involves collaborating with policymakers and local organizations to address underlying structures that suppress health in communities of color.

At the Brigham alone, health equity grants totaling more than $4.5 million support community-led programs across Boston—strengthening resources for mental health and wellness, housing advocacy, and employment and job skills development for residents. MGB recently invested $50 million to improve mental health services, workforce development, chronic disease management, and nutrition security in underserved communities. Financial investment is just a start. Health equity leaders insist deeper culture and systems change is equally imperative.

“To make lasting and measurable differences in health outcomes in the communities we serve, we need to lean in and be deliberate, disciplined, and accountable,” says Taveras.

Bridging inequities

Only four square miles in size, Boston’s Jamaica Plain (JP) neighborhood is a microcosm of the city’s demographic extremes. Stark inequities exist between the historically Black and Latinx communities and its increasingly white, affluent population. While JP’s mostly white Jamaica Pond-area households earn an average of $179,000, the average family income in predominantly BIPOC households near Jackson Square is $31,000, according to U.S. Census data (2021 estimates).

And the scales keep tipping. The 2020 census found the share of white JP residents grew from 53% in 2010 to 80% in 2019. During that same decade, the median price of a home in JP skyrocketed from $363,000 to $750,000. When the Brigham’s Center for Community Health and Health Equity conducted community-wide surveys in 2019, affordable housing was the top concern on residents’ minds, affecting everything from work and educational opportunities to air quality and green space.

“Every part of JP is experiencing gentrification, and the effects show up in data for the roughly 30,000 people living in our census tracts,” says Abigail Ortiz, MSW, MPH, co-director of racial justice and equity initiatives at Southern Jamaica Plain Health Center (SJPHC), one of the Brigham’s two community-based health centers.

“Compared with other Boston neighborhoods, JP is faring better in terms of health outcomes for conditions like asthma and diabetes,” Ortiz says. “And while that sounds great, we know it’s not necessarily BIPOC folks who are doing better.”

Ortiz runs SJPHC’s Health Promotion Center, which offers a movement studio, youth groups, and other wellness programming to SJPHC’s 13,000 patients. It is also the home base for the health center’s racial justice and equity work in the local community—and the Brigham community, too.

“It’s easy to talk about the structural racism that exists out there, somewhere else; it’s a lot harder to talk about it within your own institutions,” says Ortiz. “As a health center, if we know low-income Caribbean Latinx patients have higher rates of diabetes, the first thought might be to teach them nutrition or cooking lessons. But that would be ignoring the data.”

Ortiz describes the phenomenon in public health called the immigrant paradox: As immigrant families resettle in the U.S., their rates of chronic disease and behavioral health disorders often dramatically increase, even rippling through second- and third-generation children. Experts link these adverse health outcomes to the socioeconomic disadvantages many foreign-born Americans face.

“If we consider that our patients were healthier on the islands and then got sick once they moved here, would we hire a nutritionist to teach a cooking class, or would we hire one of our patients to come teach us how to cook Caribbean food?” Ortiz says. “These are the kinds of questions we ask: How would a racial justice nutrition program work? How would a racial justice diabetes intervention program look?”

Different by design

SJPHC and its sister health center across town, Brookside Community Health Center, were founded in the 1970s. On the heels of the civil rights movement, thousands of community health centers opened across the nation to ensure all neighborhoods, especially those neglected due to racism and classism, had access to essential healthcare services.

Today’s community health centers are still striving to close persistent health equity gaps. They are also leading some of the most innovative, thoughtful racial and social justice work in medicine.

Compared with traditional primary care centers, Brookside and SJPHC are different by design: Nearly all staff are bilingual and bicultural, the doors are open to all, and financial counselors are available to connect uninsured individuals with coverage so they can be seen. Center leaders are explicit and intentional about pursuing racial justice, and they believe everyone benefits when healthcare is designed for people with the least advantages.

“As a team, we focus on addressing the impacts of structural racism and implicit bias on our community,” says Mimi Jolliffe, executive director of Brookside. “Each of us views life through our own lens, and it is important that we are intentional about acknowledging and addressing our own biases so that we can more effectively create a trusted healthcare environment that works not only for our predominantly Latinx patient population but for all patients.”

Take specialty care, for example. Navigating costly or complex procedures can be difficult for even the most well-resourced patient. But for non-English speakers and individuals who have low income, rely on public transportation, or live with a disability, the challenges can be insurmountable. So Jolliffe and her team work to bring more specialty services in-house at Brookside, where the center’s adult and pediatric patients can receive most of their care under one roof.

“We know patients are more likely to come if they can access specialty services in the same spaces where they are used to receiving care—a place and people they trust,” she says. “When we refer patients externally, only 40% to 50% of them make those appointments. It’s one thing if patients aren’t moving forward with something elective or non-urgent, but many issues become chronically worse without specialty treatment. So we are thinking of ways to build partnerships to expand the number of specialists practicing within our walls.”

Since it first opened, Brookside has offered adult, family, and pediatric medicine as well as midwifery, gynecologic surgery, mental health counseling, dental care, and nutrition services. Brookside also partners with Brigham physicians to offer cardiology, pulmonology, and nephrology, and is working to bring in other specialties, like ophthalmology and physical therapy.

“Because we also offer pediatrics at Brookside, we are eager to partner with pediatric specialists from across the system to better serve our kids within our walls,” says Jolliffe. “We know the more specialty services we can provide with providers our patients trust, the better we will be able to meet their healthcare needs.”

Stepping up

From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, neighborhoods where Black and Latinx families live have experienced higher rates of infection, hospitalization, and death.

“The pandemic exacerbated social inequities that already existed, which further deepened the health inequities,” says Margaret Cole, MBA, BSN, RN, nurse director of Brookside. “COVID-19 rates were much higher in communities of color compared to those that are white and affluent. At Brookside, we saw more people who lost their jobs or couldn’t stay home and quarantine lest they not be able to put food on the table. On top of all that, access to testing was challenging: many sites were drive-through only and inaccessible by foot or public transit.”

Recognizing the need to better support communities at greatest risk, Brookside brought services where patients live. The health center’s leaders organized testing sites in Hyde Park, Roxbury, Mattapan, Dorchester, and Jamaica Plain. They opened vaccine clinics in non-medical spaces like the Strand Theatre, a Dorchester landmark. Brookside became one of several home bases for a fleet of community health vans in the Boston area.

“We provided care in a warm, welcoming way, in multiple languages,” Cole says. “We removed as many barriers as possible—no appointment, insurance, or ID needed. Just show up as you are, and we will help you.”

While testing and vaccinating patients at the mobile clinic, staff also asked patients if they had enough food at home or needed medications, or if they were at risk for intimate partner violence. They handed out hand sanitizer, masks, bags of fresh produce, and set up home deliveries for meal programs and prescription refills. They registered people to vote. During the summer of 2021, the mobile clinic served as many as 500 walk-in patients a day—making it an invaluable resource in the city’s ongoing efforts to contain COVID-19.

In the earliest days of the pandemic, Jolliffe and her team called Brookside’s patients to address prescription needs, screen for social determinants of health, and check in during lockdown. Anyone would benefit from this level of attention and sensitivity. But for vulnerable patients, the extra support was a lifeline.

“After 50 years, Brookside has built a trusting relationship with our community, and we want to build on that and continually push ourselves to do better, to be better,” Jolliffe says. “We want to provide healthcare in a way that each patient feels respected and supported.”

Improving care for everyone

At SJPHC, the team has spearheaded antiracism efforts for decades. The center’s Adaptive Leaders for Racial Justice model, which develops clinicians’ understanding of the root causes of racial health inequities, is so robust that it was adopted in 2021 by the American Medical Association.

SJPHC is beginning to use racial equity impact analyses, which is the same idea as an environmental analysis of traffic, pollution, and noise. Any new policy, procedure, or space improvement proposal goes through this analysis to see how racism operates in healthcare. Such efforts are informing broader hospital decision-making around equitable care—helping project planners across the Brigham think through whether potential care improvements would benefit patients of color as much as white patients.

Ortiz says that designing and leading racial justice efforts at SJPHC is about making outcomes better for everyone.

“This is not about white people taking care of people of color,” says Ortiz. “If we design the health center’s policies, practices, and structure to work for a Black transgender woman who uses a wheelchair or an undocumented person, it’s going to work better for everyone.”

This process is called designing from the margins, she explains.

“Unlike a lot of other primary care practices, the health center is open evenings and weekends,” says Ortiz. “For me, as a person with lots of structural advantages, I still benefit from those flexible hours, even if I don’t need them the way other patients and families do. When Black women are good in the healthcare system, I’m going to be good, too. That is racial justice and liberation.”

Dennie Butler-MacKay, LICSW, is the senior clinical social worker at SJPHC. She provides psychotherapy for individuals and families and co-directs racial justice and equality initiatives at the center.

In community health settings, behavioral healthcare for BIPOC patients is elusive, Butler-MacKay notes. With partial programs and other social services closing in communities across Massachusetts, the few available resources are designed to respond to crises, without the full context and contours of patients’ lives.

“We have a powerhouse group of behavioral health professionals who access hefty trauma-informed practice with the latest clinical approaches,” says Butler-MacKay. “We want our trauma treatment to be state of the art. We bring in treatment approaches and frameworks from across practices and communities, including sensorimotor psychotherapy, internal family systems, somatic abolitionism, embedded social justice, and meditation.”

At SJPHC, Ortiz and Butler-MacKay embrace any chance to explicitly confront racism, an approach they lament still feels radical in healthcare. Through the racial justice and health equity training they lead, they relish opportunities to help others—especially those with advantage—become more attuned to how inequity harms us all.

“Racism is race-based trauma,” Butler-MacKay says. “That trauma is more acute and health harming for people of color. But white people feel it, as well. We all have to metabolize what our bodies have been explicitly holding.”

She adds, “It’s a liberation practice, and it’s much more accessible than you might think. This isn’t a program; it’s a movement. And it has to include the body. You have to be able to feel, in order to heal, in order to deal, in that order, for long-standing change.”

Partnering for impact

The success of the Brigham’s community health efforts owes much to the passion and dedication of individuals stepping up and responding to the city’s needs. But in a nation that spends significantly more on healthcare than other developed countries, with the worst outcomes, lasting gains in health equity depend on systemic investment and organizations coming together and working differently.

“To meaningfully change healthcare so it works better for everyone, we must address the underlying inequities and social infrastructure of our communities,” says Cole. “We have to invest in our neighborhoods, partner with local organizations, and increase access to the things that make a difference on an individual level: healthy foods, truly affordable housing, green spaces, early childhood education, affordable childcare, and better job opportunities.”

Taveras says now is a pivotal time to think big in terms of community outreach and interventions. With $250 million in funding dedicated to community health in the American Rescue Plan, she is excited to see those dollars foster more collaboration across Boston’s healthcare, government, and nonprofit ecosystems.

“We are fortunate to have many local community-based organizations and healthcare institutions to make a collective impact,” she says. “We understand our own responsibility in the community and are excited to have resources coming down the pipeline for us to share in improving the well-being of everyone in our city.”