For the tens of thousands of people on transplant waiting lists, being matched with a donor is a joyous milestone to a life of new possibilities. But transplants also spark a lifetime of health challenges related to balancing the immune system’s responses to the new organ, limb, or tissue it sees as foreign. For the chance of extended, healthier lives, transplant patients must take daily regimens of immunosuppressant drugs and risk complex side effects and rejection. This balancing act begs the question: Is the immune system friend or foe?

Taylor MacLean was just 25 years old when she learned she needed a new heart. Diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy in her early 20s, MacLean’s diseased heart muscle couldn’t pump blood efficiently. Although her transplant surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) nearly two years ago was a success, she has been plagued recently by serious gastrointestinal (GI) issues.

Gut check

“My Brigham doctors are working hard to figure this out,” MacLean says. “We explored my diet, lifestyle, and whether I’ve developed a tolerance to the medications that suppress my immune system so my body can accept the new heart. I’m happy there’s no sign of a brewing infection or drug intolerance, but I can’t help but wonder what’s causing these GI symptoms.”

Such health mysteries are common for transplant recipients. After a transplant, a patient regains good health, and then, seemingly out of nowhere, a persistent illness such as GI distress can strike.

“It’s possible that when we use heavy immunosuppressive treatments to create the immune suppression a new organ needs, we may also create unintended problems in the gut, which prevent the body from either adapting favorably to the organ or maintaining overall health,” says Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, medical director of the Heart and Vascular Center.

Mehra hypothesizes that MacLean’s GI symptoms could relate to how her immunosuppressive drugs affect her gut microbiota (the millions of microorganisms and bacteria living in our guts) and their relationship to her immune system. He hopes to uncover effective forms of relief for patients like MacLean whose post-transplant symptoms have no obvious cause. Eventually, he’d like to prevent such health issues from happening at all.

Until then, MacLean must wait and see if her mysterious post-transplant symptoms will disappear on their own.

Questioning assumptions

More than 30,000 organ transplants are performed each year in the United States. But this now standard treatment was long thought impossible because of the immune system’s rejection of foreign bodies.

With the first successful human kidney transplant in 1954, BWH’s Joseph E. Murray, MD, demonstrated how immunosuppression could prevent rejection. This lifesaving and groundbreaking work opened the door for organ transplantation as viable treatment and earned Murray a share of the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

In the more than 60 years since Murray’s first successful kidney transplant surgery, transplant immunology has come a long way. While current immunosuppressant regimens have become more refined, Mehra and other researchers are finding that, over time, some people’s immune systems adapt naturally—without medical intervention—to accept a new organ or body part.

“One study conducted in humans looked at a female heart in a male recipient,” Mehra explains. “When the male recipient later died and they examined the DNA of that heart, the female heart had taken on male heart features.”

This phenomenon is known as chimerism, in which an individual comprises two genetically distinct types of cells.

“This means there is a form of immune chimerism that may facilitate some degree of immune tolerance,” says Mehra. “It’s a concept that needs to be evaluated further. How does the host change the foreign body to be more like it? We want to find out.”

Mehra and his colleagues are questioning assumptions about the immune system by exploring how the body adapts and changes the transplanted organ or tissue to be more like itself.

“This information could ultimately change patients’ care over the long term, as their bodies begin to accept the new organ,” he says.

Beyond rejection

Anil Chandraker, MD, medical director of Kidney and Pancreas Transplantation and director of the Schuster Family Transplantation Research Center at BWH, shares Mehra’s belief that the immune system’s abilities go far beyond attacking foreign objects.

Chandraker notes many kidney transplant patients recover beautifully on very low doses of immunosuppressants. Some kidney transplant patients who took themselves off all immunosuppressive drugs—against medical advice—have not only survived, but thrived.

While Chandraker strongly urges patients not to take this risk, he emphasizes that these unusual cases illustrate how some immune systems’ regulatory T cells—which help the body to suppress an overreaction to foreign objects—can adapt on their own to accept a new organ.

“The immune system can make some accommodations to accept the transplant,” he says. “In some cases, the patient’s body naturally achieves a balance between the aggressive T cells trying to reject the organ and the regulatory T cells trying to accept it.”

Chandraker is attempting to recreate this natural immune response in his lab. With successful studies completed in rodent models, Chandraker’s next step is to test T-cell therapy in clinical trials, which could enable his team to create individualized treatments to boost and balance each enrolled patient’s unique immune response in the years to come.

“We want to expand a transplant patient’s regulatory T cells, recreating the positive natural results we witness occasionally in patients who stop using their medications,” says Chandraker. He refers to this as “tilting the immune response” to accept transplanted organs, limbs, or tissues naturally, without requiring traditional, lifelong immunosuppressive drugs.

Spying on cells in real time

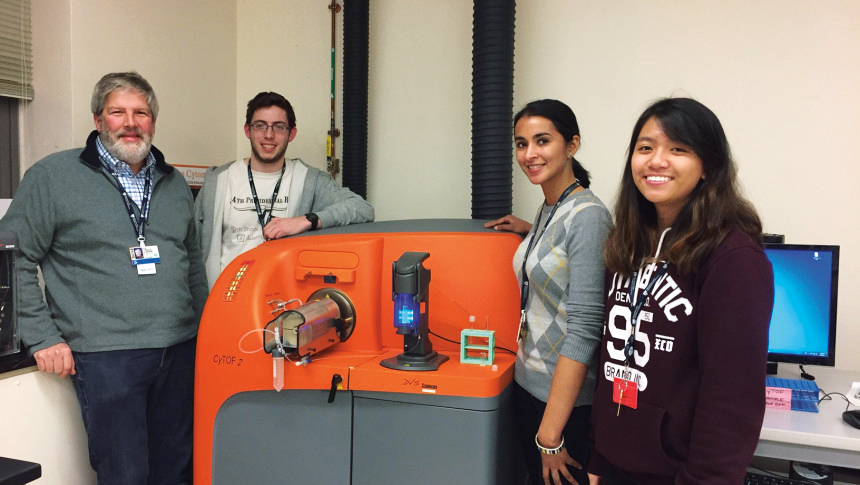

To tilt the immune response, scientists need to examine cells’ behaviors and characteristics in real time. This was not possible at BWH until 2013, when the hospital joined other medical centers in purchasing CyTOF, the only commercially available technology of its kind that can process a blood or tissue sample and immediately observe the intricate workings of the present T cells.

“With CyTOF, you can find out just about everything you need to know about what types of immune T cells are in a specimen,” says Chrysalyne Schmults, MD, director of the Mohs and Dermatologic Surgery Center and program director of Micrographic Surgery and the Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship Program. “You can look at the T cells around a tumor, infiltrating into a tumor, or circulating in a patient’s blood, and see exactly what kind of immune cells there are.”

Schmults explains an interesting phenomenon that CyTOF technology can track.

“Some T cells attack, while other T cells regulate and tell them not to attack,” she says. “However, they can switch their roles. CyTOF helps you know when this switch happens.”

Such detailed knowledge enables researchers to understand, in real time, why and how certain immunosuppressive drugs are working.

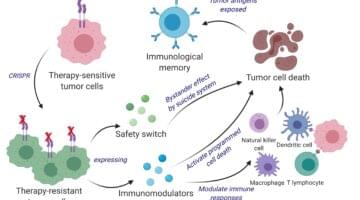

CyTOF will help pave the way for T-cell therapies, as well as the design of drugs that can influence the immune system to attack only bad cells—such as cancer—without provoking organ rejection or requiring system-wide immunosuppression. Oncologists are already using CyTOF to modify patients’ own aggressive T cells in the lab and reintroducing them into the body to attack cancers.

Tailoring immunosuppression

Stefan G. Tullius, MD, PhD, chief of transplant surgery and director of the Transplant Surgery Research Laboratory at BWH, is eager to see the vast potential of individualized immunosuppression realized.

“In the future, we will use molecular biology methods to better assess each individual’s risk for rejection and select certain immunosuppressants based on a person’s age and profile,” Tullius says.

He believes understanding the aging immune response will become critical when customizing post-transplantation treatments.

In the future, we will use molecular biology methods to better assess each individual’s risk for rejection and select certain immunosuppressants based on a person’s age and profile.

Stefan G. Tullius, MD

“The aging immune system parallels our cognitive capacities,” Tullius says. “Just as our brains accumulate a lot of experience as we get older, our immune systems accumulate a lot of immune memory. But in both cases, as we age we become less capable of effectively using this memory.”

When we age, the immune system spurs an immune response that might be more likely to reject an organ, instead of creating a helpful, adaptive immune response that would encourage the body to accept the organ.

“This obviously leads to a very different concept on how we treat older versus younger transplant recipients,” Tullius says. “Older patients need different medications. The observations we make in the clinic and bring to the lab for further study will allow us to adapt immune suppression according to age.”

More than skin deep

Skin cancer is one of the most dramatic side effects of immunosuppressive drugs. Patients with successful organ transplants often become especially susceptible to developing squamous cell carcinoma of the skin (SCC), the second most common skin cancer.

“SCC is usually curable with surgical removal in healthy, non-transplant patients,” says Thomas Kupper, MD, chair of the BWH Department of Dermatology. “In immunosuppressed patients, the same cancer acts much more aggressively.”

Kupper cites a recent study from Australia showing that 25 percent of mortality cases in transplant recipients were due to metastatic skin cancers. He believes this dramatic difference in how skin cancer behaves in healthy versus immunosuppressed people may be due to immunosurveillance, in which the immune system constantly monitors tissues for foreign cells.

“The healthy immune system sees that budding cancer and attacks,” he says. “In healthy people, we think a lot of skin cancers are killed before they even become clinically evident. If the immune system is not working well, you start developing many more of these cancers that well-functioning immunosurveillance would have rejected before they ever got a chance to take off.”

Finding equilibrium

Kupper likens transplant immunosuppression to walking a tightrope.

“If you enhance the immune system too much, you risk organ rejection—but you’d like to do something to reduce this hugely increased risk of skin cancer,” he says.

Fortunately, skin cancer can be caught early with preventive monitoring, so BWH doctors recommend that transplant patients visit a dermatologist regularly. In addition, Kupper says medications such as rapamycin can help the body avoid organ rejection while lowering skin cancer risk by as much as 50 percent.

“This is the best we can do now—and we are always looking at what other medicines could better suppress the formation of skin cancers,” Kupper says.

Kupper feels confident that BWH’s continuing innovations in immunology and transplant medicine will lead to dramatically improved treatments and better overall health for organ recipients.

“The Brigham is blessed with physician-scientists who understand both patients and diseases, and know the most advanced scientific approaches to diagnosis and treatment,” says Kupper. “You get wonderful cross-talk between complex patient cases and cutting-edge scientific concepts. This creates a wonderful engine for innovation and discovery.”

Will Lautzenheiser, left, with his immunologist, Anil Chandraker, MD

Will Lautzenheiser, left, with his immunologist, Anil Chandraker, MD

(Photo by Stu Rosner)

NEW ARMS AND A NEW NORMAL

In 2011, a vicious bacterial infection swept through Will Lautzenheiser’s body. Soon after, an attack of flesh-eating bacteria required him to be flown from Montana to Utah, where surgeons amputated Lautzenheiser’s arms and legs to save his life. He then spent five months recovering in intensive care.

In 2014, a 35-person medical team from Brigham and Women’s Hospital gave Lautzenheiser a chance at regaining mobility and independence by successfully transplanting a deceased donor’s arms. Afterwards, he completed 18 months of intense occupational therapy and must take a daily regimen of immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of his life to help prevent limb rejection.

“It’s a hard decision to go on immunosuppression when you’re otherwise healthy,” says Lautzenheiser. “Unlike organ transplant patients, amputees usually are not sick or dying. It can be a tough decision to purposely make oneself unhealthy in order to improve quality of life by having limbs restored as much as possible. For me, this was a great decision. Some might choose otherwise.”

He empathizes with amputees who decide not to undergo a limb transplant due to the potential increased risks of diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and other illnesses that can emerge due to a suppressed immune system. Fortunately, Lautzenheiser hasn’t yet experienced significant side effects from the immunosuppressive drugs, but he is realistic about what could happen.

“The longer I’m on them, the more damage they will likely do,” he says. “But the life expectancy of a quadruple amputee is already shortened because of circulation issues—so it wasn’t that difficult a decision. My immunologist, Dr. Anil Chandraker, reassured me things could be managed. So far, he’s been right.”

Lautzenheiser undergoes regular blood work and biopsies so his doctors can look for signs his immune system may be planning to attack his new arms.

“Initially after the transplant, the blood work was daily,” he says. “Now, it’s once every three months.”

Despite the challenges of recovery, Lautzenheiser says he would not trade his remarkable journey.

“What does immunosuppression really mean? And how over the long term is it affecting me? These remain the big questions,” he says. “It makes me think about how precious life is, the incredible gift to be on the receiving end, and the generosity of donating. It goes beyond magnanimity. It’s a beautiful act. I’m so grateful for what I’ve been given, it’s worth the uncertainty.”