Two years ago, Meghan Gabel was a typical 21-year-old college student planning her dream trip: a semester abroad in London. Her dream was jeopardized when, seemingly without reason or injury, her feet began to ache with searing pain. She visited her local physician, who treated her for plantar fasciitis, a common and usually temporary source of heel and foot pain.

But the pain was unrelenting, and spread to Gabel’s shoulders, arms, and wrists. Her physician ruled out Lyme disease, but still couldn’t pinpoint the cause. Finally, she found her way to Michael Weinblatt, MD, co-director of clinical rheumatology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH). Weeks after the initial flare of foot pain, Weinblatt diagnosed Gabel with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), one of the most common autoimmune diseases.

“With these diseases, it’s not uncommon for the right diagnosis to take four, five, or more tries because of the vague symptoms,” says Weinblatt. “This is especially the case in young people—particularly young women.”

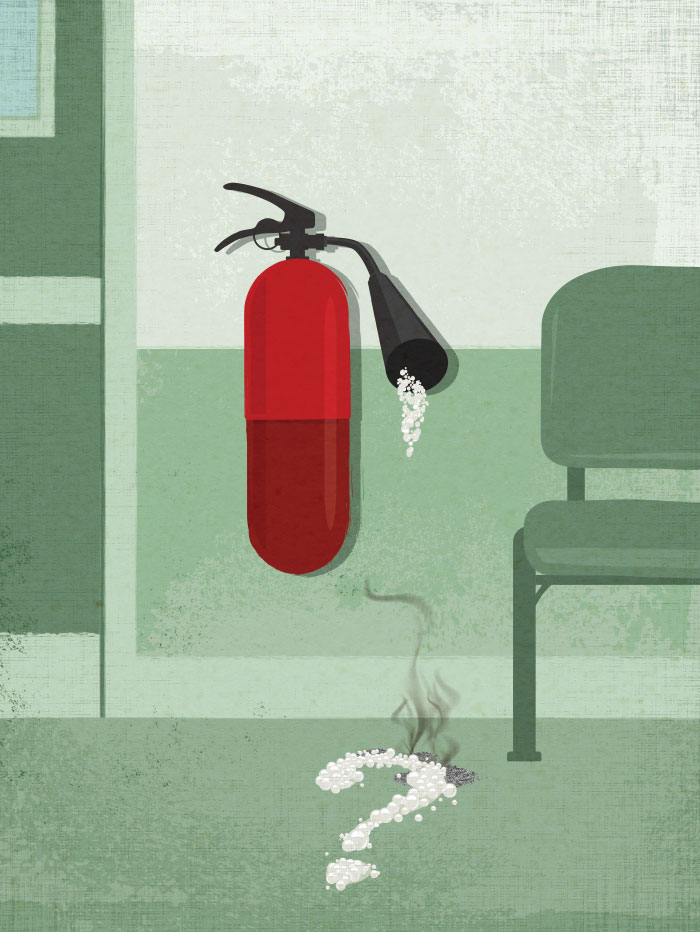

Where there’s smoke

Autoimmune diseases emerge when the immune system perceives a nonexistent threat and responds by hijacking normal processes in the body. In RA, immune malfunctions attack and inflame the body’s joints. In Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, the immune system blitzes the lining of the intestines. In lupus, it zeroes in on the lining of the lungs, heart, and kidneys, as well as the joints and eyes. It targets nerve cells in multiple sclerosis, the skin in psoriasis, and triggers hundreds of puzzling manifestations in at least 80 other autoimmune diseases.

“There is a misconception that people don’t die from these diseases, and they are benign,” says Weinblatt. “We know that if left untreated, autoimmune diseases lead to life-threatening complications.”

By tracking 1,400 RA patients in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Rheumatoid Arthritis Sequential Study (BRASS) registry since 2004, many collaborators, including Weinblatt and rheumatology investigator Nancy Shadick, MD, MPH, have gleaned information about which treatments work—or don’t work—for each person and whether other serious conditions develop.

“We know from the BRASS registry that 10 percent of patients with RA will have significant lung disease and 30 percent more will have lung scarring or inflammation,” says Paul Dellaripa, MD, co-director of the Interstitial Lung Disease Clinic at BWH. “Once systemic inflammatory diseases involve the lungs, some patients have the same survival rate as with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. We are starting a clinical trial to examine the unique signature in RA patients that seems to indicate their risk for developing lung disease.”

People with RA also experience twice the normal risk of dying from a heart disease. This was confirmed in 2002 when Peter Libby, MD, former chief of cardiovascular medicine, and Paul Ridker, MD, director of the Center for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention, observed that inflammation in blood vessels contributes to atherosclerosis.

“BWH pathology investigators also showed that people with raised inflammatory markers have cardiovascular events earlier in their lifespan—sometimes in their 30s, 40s, and 50s,” says rheumatologist and drug safety expert Daniel Solomon, MD, MPH.

Solomon is now working with Ridker on a major clinical trial to examine cardiovascular scans of hundreds of patients with RA—some taking methotrexate, some on biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapies like adalimumab and etanercept, and some on combined therapies—to see how these different rheumatology treatments affect cardiovascular health outcomes.

On good days with no RA flare-ups, I might forget I have arthritis, but then a morning comes when a five-minute walk across campus turns into an hour-long ordeal.

Meghan Gabel

Twice burned

Gabel, now 23, was shaken by her RA diagnosis. “I had never met a young person with arthritis,” she says. “I had this image of it as the disease that ruined my grandmother’s hands. When my mom told me my grandma has had RA since she was 25, it really hit me.”

While the tendency of autoimmunity to run in families helped explain how Gabel developed RA, there was another factor. Just before her 13th birthday, she was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune disease that restricts her body’s ability to produce insulin, an energy-regulating hormone. People with one autoimmune disease commonly develop others.

“I’m always thinking about diabetes,” says Gabel, citing her routine of careful eating, insulin injections, and blood glucose monitoring to keep her blood sugar stable. “But even on my worst days with diabetes, it never holds me back from being active and doing the things I love. RA is different. On good days with no RA flare-ups, I might forget I have arthritis, but then a morning comes when a five-minute walk across campus turns into an hour-long ordeal.”

Gabel says her diabetes and arthritis “don’t always play nice together.” RA increases her blood sugar levels and diabetes lowers the effectiveness of her RA medications. When she worried she wouldn’t be able to get her diseases under control in time to take a term abroad, Weinblatt told her, “Those are our problems to solve. We are going to get you to England.”

Hot pursuit

Michael Brenner, MD, chief of the Division of Rheumatology, Immunology and Allergy, sees enormous potential in finding shared pathways among seemingly different diseases.

“Psoriasis, IBD [inflammatory bowel disease], and RA have a shared pathway,” says Brenner, who launched BWH’s Human Immunology Center in 2013 to help clinicians and scientists interested in the human immune response share ideas and access advanced research technology. “That’s why anti-TNF therapy [a newer class of drugs that stops autoimmune disease progression by blocking an inflammation-producing protein called TNF] can be used to treat all three.”

Solomon agrees. “While inflammation underpins much of disease, you don’t give immunosuppressants to everyone with inflammation. There are different pathways and biomarkers involved in each individual’s disease, and serious side effects if you get it wrong. When there are overlapping pathways, and you create a drug that targets those pathways, that’s when you get blockbuster treatments like methotrexate and adalimumab that can treat several different diseases for many different people.”

For Gabel, the right combination to wrangle her RA in time for her London trip was a regimen of the anti-TNF therapy etanercept, low-dose prednisone, and naproxen. The combination meant she could endure long walks around the city—but not without tucking honey packets in her shoes first, in case her glucose levels dropped too low.

Scorched earth

Like Gabel, MaryJo Marra-Hauser’s complicated medical odyssey began in college. She had red spots all over her legs and she felt tired and feverish all the time. First her doctors thought it could be mixed connective tissue disease, and then Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The correct diagnosis of lupus came at age 21, after a vicious hives-like flare landed her in the hospital. Since then, she has seen numerous specialists near her home in Connecticut to treat her lupus and its many complications.

“Doctors today know so much more than they did then,” she says. “I was pumped with steroids in the hospital to control the flare, and then I continued to take them for 20 years until I had a heart attack at 41. My cardiologist told me my veins and arteries were so brittle from the steroids that they couldn’t put a stent in, so I had to have double-bypass surgery.”

Like a third of people with lupus, Marra-Hauser is also battling kidney disease. Fifteen years ago, physicians told her she would need either dialysis or a kidney transplant. So far, she has avoided this fate by taking medication, working out five to six days a week, practicing yoga, and eating an all-organic diet free of red meat, artificial ingredients, and alcohol.

Referred to the Brigham and Women’s Transplant Center by her Connecticut cardiologist, Marra-Hauser has been on the deceased donor list for nearly a year. However, the waiting list for a deceased kidney donor can be up to seven years long, so Marra-Hauser is working with BWH in hopes of being matched with a living kidney donor.

“I never expected to be on this journey,” says Marra-Hauser. “It’s hard living far away from Boston, but if I have to go through this process of finding a kidney donor to avoid dialysis, I’m glad to do it with Brigham and Women’s.”

Sifting through ashes

“People who have had lupus for the longest time have really seen the ravages of this disease, particularly from long-term corticosteroid use without other management,” says Karen Costenbader, MD, MPH, director of the Lupus Program at BWH. “We have better options today, but we still don’t have many approved treatments exclusively for lupus. We borrow from rheumatology, oncology, nephrology, and other areas to get the alchemy right for each patient’s disease.”

Though lupus is highly variable, Costenbader says the first-line treatment they recommend is an anti-malaria medication. The quinine-based compound was adopted into treatment after physicians in the 1950s found it suppressed the inflammation at the source of many lupus symptoms.

“It’s not a miracle drug, but it improves rashes and fatigue, brings down cholesterol, and may prevent cardiovascular disease, thrombosis, kidney disease, and even pregnancy complications,” she says.

Since 90 percent of lupus patients are women, Costenbader’s research team is also pursuing leads into the disease’s hormonal and environmental instigators, including smoking, obesity, contraceptives, diet, and stress.

Sending up flares

Repurposing drugs for other diseases is a common strategy among physicians who treat people with autoimmune disorders. Weinblatt was a newly minted rheumatologist at BWH in the 1970s when he first learned of small-scale studies showing the inflammation in RA appeared to be blocked by low doses of methotrexate, a cancer chemotherapy drug. It was the first RA treatment that leaped beyond symptom management to physically change the disease.

The Brigham is the center of the universe for studying autoimmune diseases. Often the problem is knowing which question to attack first.

Karen Costenbader, MD, MPH

But what seemed like a promising breakthrough hit one dead end after another. To Weinblatt’s dismay, many rheumatologists were reluctant, some even outright hostile, to recommend a cancer drug to their RA patients. It took the field more than 20 years before coming around to conduct formal studies with this drug. Weinblatt and colleagues designed one of the first clinical trials of methotrexate, published in 1985.

“By 1989, methotrexate was the first-line treatment for RA, and 30 to 40 percent of patients taking it showed low or no disease activity with remote risk of adverse side effects,” says Weinblatt. “Together with other investigators of methotrexate, we changed the course of history for this disease.”

Kindling hope

Autoimmune disorders defy medicine’s traditional organization into distinct organ- and disease-specific departments. As a result, Brenner believes that opening the resources of the Human Immunology Center to anyone pursuing questions about human immune response will help break down walls separating researchers and clinicians working on autoimmunity and inflammation in their respective fields.

“We have a chance to apply our work further than autoimmune diseases to disorders you wouldn’t know have underlying inflammation, like obesity, type 2 diabetes, emphysema, HIV, and hepatitis,” Brenner says. “Inflammation is not a rheumatology problem alone. Our vision for the Human Immunology Center is for it to be cross-cutting, and to take a broad approach to solving human disease.”

With opportunities to collaborate and trade insights with BWH experts in virtually every area of medicine, Costenbader says, “the Brigham is the center of the universe for studying autoimmune diseases. Often the problem is knowing which question to attack first.”

Deepak Rao, MD, PhD (left), and Michael Brenner, MD, diagram the process of inflammation.

(Photo by Len Rubenstein)

DISEASE DECONSTRUCTION

Michael Weinblatt, MD, hopes momentum in precision medicine can be translated for his patients in rheumatology.

“Oncologists can impact some cancers without destroying healthy cell functions,” says Weinblatt. “This is where I hope we can go with RA and related diseases: target specific sources of inflammation without destroying the healthy processes of the immune system.”

His vision may be close at hand. Using advanced cell-sorting technology, RNA sequencing, and other powerful instruments to examine tissue from patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Deepak Rao, MD, PhD, Michael Brenner, MD, and their collaborators traced disease activity to a specific subset of T cells.

In healthy immune response, T cells help B cells create antibodies against harmful substances that enter the body. Rao and Brenner saw high quantities of an unusual T cell subset that accumulates in the joints of patients with RA. They posit that specifically targeting this T cell subset in RA patients will reduce inflammation in the joints but preserve the rest of the T cells that fight infections.

“We achieved this through a process called disease deconstruction,” says Brenner. “Rather than go in with a hypothesis as to which cell, pathway, or cytokine is causing the inflammation, we looked at a hundred different markers of disease in tissue samples to determine the specific disease characteristics for each patient.”

Rao sees this work as tugging on a thread that could unravel the pathology of many diseases, not just RA.

“RA is a compelling disease for immunologists to study because it involves chronic inflammation driven by many different components of the immune system,” he explains. “We also understand the genetics incredibly well, we can study the affected tissue, and we even know some of the relevant antigens [the specific proteins that produce inflammation]. We’re now excited to look for these pathologic T cell subsets in other autoimmune diseases too, including lupus and multiple sclerosis.”