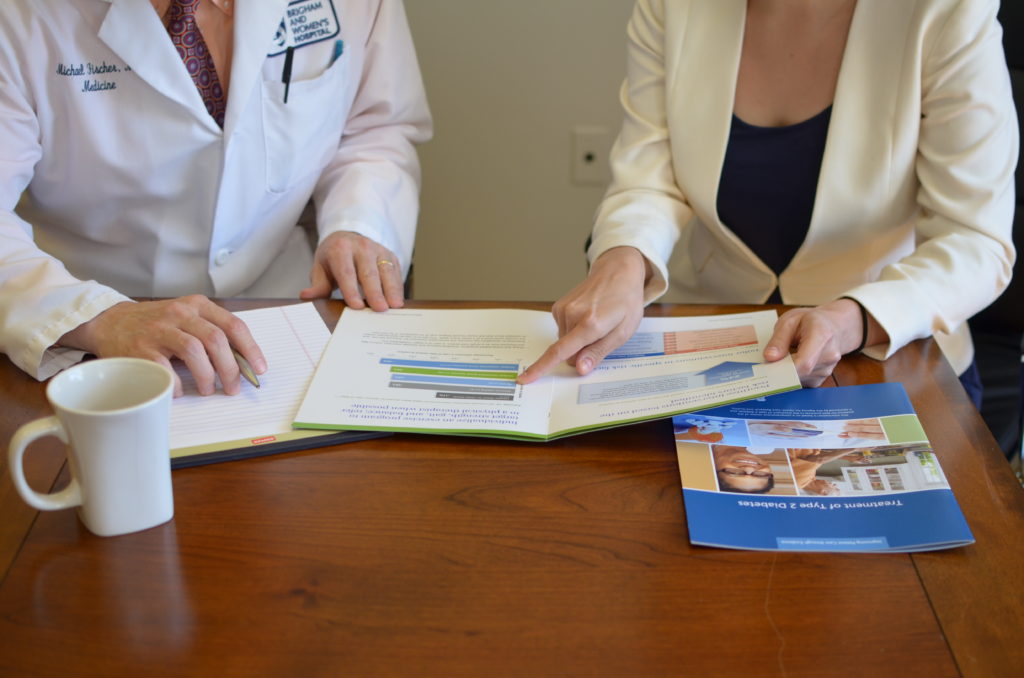

The practice of pharmaceutical sales representatives meeting individually with physicians to promote brand-name medications is called drug detailing. And while drug detailing is increasingly scrutinized and regulated, it is still common for pharmaceutical representatives to visit medical offices to distribute promotional materials and goods to persuade physicians to prescribe their products.

To provide clinicians with a more balanced source of information, Michael Fischer, MD, MS, a primary care physician in the Phyllis Jen Center and faculty member within the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, teamed up with Jerry Avorn, MD, in 2010 to create the National Resource Center for Academic Detailing (NaRCAD). The goal: help clinicians make prescribing decisions based on evidence rather than marketing. The year NaRCAD was founded, the pharmaceutical industry spent an annual average of $20,000 per physician on marketing efforts.

“The difference with academic detailing is we’re not trying to secure a doctor’s commitment to pad our bottom line,” says Fischer. “We are solely interested in commitments to patients’ health needs and experiences.”

After their studies confirmed that the outreach model is helpful to clinicians, the NaRCAD team set out to train health educators across the country to have evidence-supported conversations with physicians about prescribing. To date, they have trained 500 academic detailers.

“You can’t change ineffective prescribing behavior until you are in front of physicians, asking why they aren’t following guidelines,” Fischer says.

“Often clinicians are overburdened and struggle to keep up with the literature on top of their heavy caseloads, especially in primary care.”

At first, NaRCAD focused on mainstay community health topics, from tackling heart disease to increasing vaccination rates. Soon, pain management and the opioid crisis came up in academic detailing conversations.

“Anyone who has practiced medicine for more than 10 years has been conditioned to treat people with the goal of reducing pain to zero regardless of how much medication it takes,” says Fischer. “The opioid crisis shows this is not the best strategy, but it’s hard to change long-held attitudes and behaviors. When I talk to clinicians, the first thing I ask is how they manage their patients’ pain, and then we talk about their approach when someone is using too much pain medication.”

Fischer is hearing dramatic success stories. To address untreated opioid addiction among veterans, academic detailers spent two years conducting targeted, unbiased outreach to physicians in the Veterans Health Administration. Their efforts led to a sevenfold increase in prescriptions for naloxone, a medication that reverses opioid overdoses.

“Now that we have a critical mass, we want to create centers to establish full-scale academic detailing training in many regions and spread locally from where they are,” says Fischer. “Their regional expertise combined with our approach will be sustainable and allow them to dive into the unique health outreach needs of their communities.”