Why do some people sail through life with few major illnesses while others begin experiencing chronic medical conditions in their 20s or even earlier?

Your health relies on a unique combination of genetics, biology, and other factors including your habits, education, and even ZIP code—from the air quality and walkability of your neighborhood to your access to healthcare.

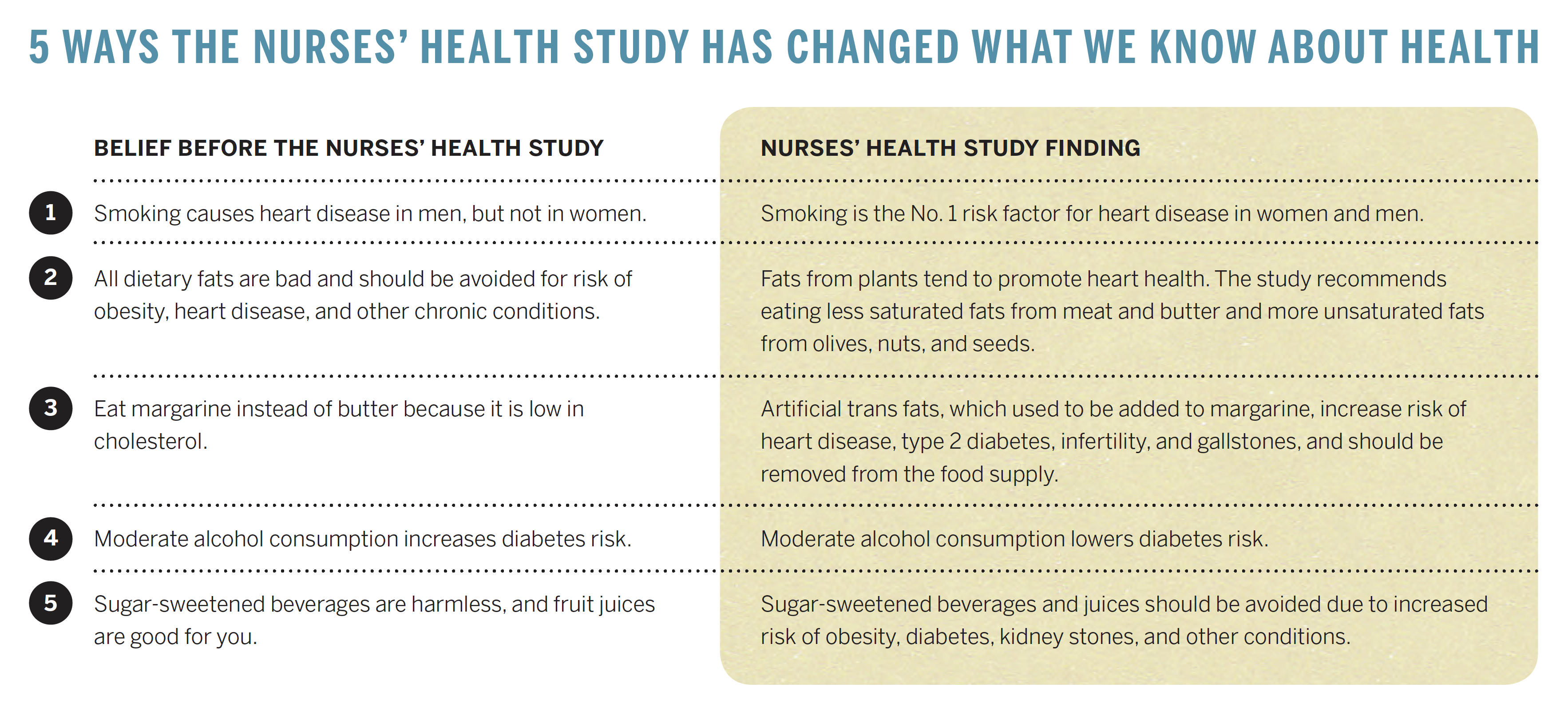

Although there is no magic formula for a long, healthy life, decades of research confirm certain behaviors improve your chances: not smoking, staying physically active, and maintaining a healthy diet. While these recommendations are practically common knowledge now, 50 years ago, that was not the case. Indeed, much of the health advice we hear today stems from a single source: the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS).

Researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital started the Nurses’ Health Study in 1976 with one goal: follow a large group of women over time to determine if oral contraception pills cause long-term effects on women’s health. When selecting a population of women to follow, the researchers thought nurses would be good participants because of their knowledge about health and reputation as a helping profession. On the first questionnaire mailed to 171,000 nurses across the United States, 71 percent responded. This is almost unheard of in population studies, where response rates typically range from 5 percent to 25 percent.

Helen Levitan, who served as a nurse in Europe during World War II, was one of nearly 122,000 women who replied to the first mailing. For the next four decades until her death at age 96, she faithfully completed the biennial survey, answering questions about her health, diet, physical activity, medications, and more.

Her daughter Jean remembers when Helen was 92 years old she complained she did not receive the questionnaire: “My mom said, ‘They probably think I’m dead, but I want to fill out the survey!’ She was proud of being part of such a significant study. So we got the missing survey, and I helped her submit it.”

Helen was not alone in her dedication to the study. Of the nurses who have joined, 90 percent continue to fill out questionnaires.

Over the past 43 years, the study has surpassed its founders’ expectations, becoming the largest and longest-running investigation of women’s health worldwide. The study now includes 280,000 women and men across three generations—NHS1, NHS2, and NHS3.

GATHERING CLUES

“In population studies like this, it’s a dream to find such motivated participants because the more data we have, the more health conditions we can study,” says Francine Grodstein, ScD, director of the Nurses’ Health Study and an epidemiologist at the Brigham.

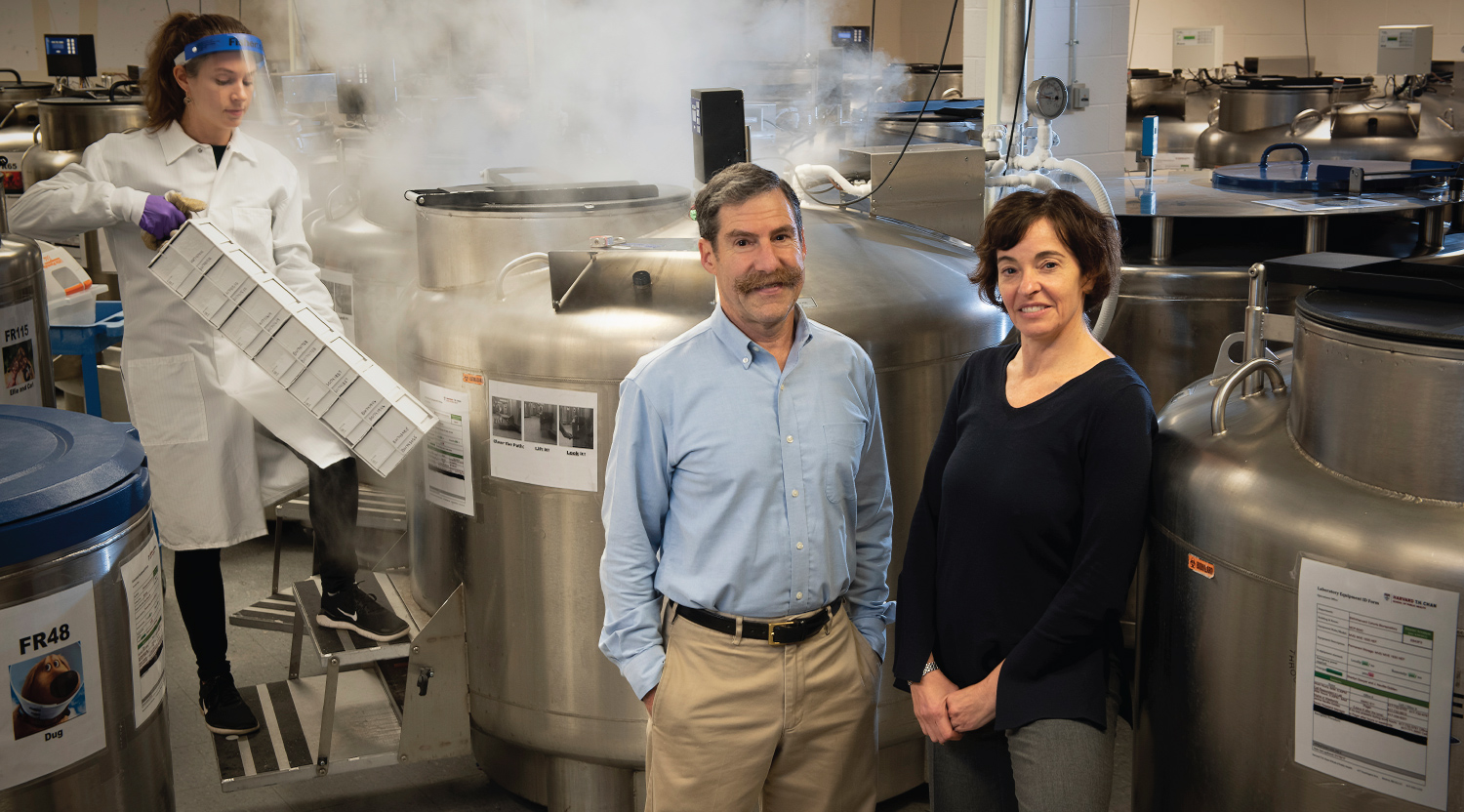

In addition to answering questionnaires, nurses provide biospecimens such as blood samples, saliva, and nail clippings, which are stored in a large biobank and used to study how biology, genetics, and lifestyle are interconnected with health.

“It was a visionary decision by the study’s founders to start collecting biospecimens years before having the technology to analyze them in a sophisticated way,” says Edwin Silverman, MD, PhD, chief of the Channing Division of Network Medicine, which employs the roughly 100 epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and other Nurses’ Health Study staff. “With current technologies, we can generate data we couldn’t have dreamed of before, giving us an unprecedented opportunity to understand the biological causes of disease and better prevent, diagnose, and treat medical conditions affecting so many people.”

[We have] an unprecedented opportunity to…better prevent, diagnose, and treat medical conditions affecting so many.

– Edwin Silverman, MD, PhD

Today, more than 1,000 researchers worldwide access data from the Nurses’ Health Study to conduct investigations. Their findings have identified many risk factors for chronic diseases, as well as ways to increase survival rates once a disease is diagnosed. They have also influenced laws, public health policies, and recommendations including U.S. guidelines on diet and physical activity.

For instance, when researchers addressed the study’s original question about the effects of contraception, they found that taking birth control pills can slightly increase the risk of heart disease, but only among smokers. This discovery helped lead to changes in prescribing practices and new formulations of the pill to make it safer.

CONNECTING NUTRITION AND DISEASE

One of the study’s landmark findings in the early 1990s showed that consuming trans fats—mostly found in partially hydrogenated oils in processed foods—increases the risk of heart disease and death. Laws slowly evolved in response, starting with revised nutrition labeling for consumers. By June 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned trans fats from the U.S. food supply.

“We estimate more than 100,000 heart attacks will be prevented each year as a result of our finding about trans fats,” says Meir Stampfer, MD, DrPH, an epidemiologist at the Brigham and longtime principal investigator for the Nurses’ Health Study. “Those 100,000 people won’t realize they’ve avoided a heart attack, and we won’t know who they are. Prevention does not get much attention in the public eye, but it is just as important as treatment, if not more so.”

This achievement with trans fats came about primarily because of the work of Walter Willett, MD, DrPH, principal investigator of the Nurses’ Health Study 2. Since 1980, Willett has sent the nurses a supplemental food frequency questionnaire, which has revealed links between nutrition and many conditions, from kidney stones to cancer.

“For a long time, people have known that being overweight is a risk factor for heart disease and diabetes, but some may not realize the connection between weight and cancer,” Willett says. “This finding came from the Nurses’ Health Study.”

More recently, Willett and his colleagues have observed that diet during adolescence has a stronger influence on breast cancer risk than diet during adulthood.

“We have seen that women who ate more red meat had higher rates of breast cancer later in life,” he says. “And a healthier diet in adolescence appears to reduce risk of premenopausal breast cancer. It’s quite important what we’re feeding our kids.”

TAMING THE SKEPTICS

While Willett’s research shows eating red meat is associated with increased rates of breast and colorectal cancer, this evidence does not prove it is a cause of the diseases. This is a drawback of population-based observational studies like the Nurses’ Health Study.

Randomized controlled trials can determine a cause-effect relationship. In these studies, participants are randomly selected for two groups. The experimental group receives the intervention being tested, and the control group gets a conventional treatment or placebo. These trials have the potential to show whether the intervention, such as a treatment or procedure, has a direct effect.

“While randomized trials are considered the gold standard of research, many decisions in public health and medicine need to be based on complementary evidence gathered in other ways, too,” says Alberto Ascherio, MD, DrPH, MPH, a Brigham epidemiologist and Nurses’ Health Study investigator who focuses on neurodegenerative diseases. “We don’t have mathematical proof that says exercise will reduce your risk of disease, but the evidence is overwhelming, right? The strength of a population study like the Nurses’ Health Study is you can track the lifestyle and medications of participants for 10, 20, or 30 years before they get a disease. That’s impossible to do in a randomized controlled trial.”

The scope of randomized trials is typically narrower than a population study as well. They usually last for several years at most and enroll far fewer participants. They also start with a single hypothesis, or prediction, to test and must focus on evidence related to that hypothesis—to the exclusion of other interesting hypotheses. The Nurses’ Health Study takes a different approach.

“We can look at many hypotheses and see if we get a signal,” says Ascherio. “Then we follow that signal and test hypotheses, one after another, showing we are onto something.”

A few years back, Ascherio wanted to show potential grant funders that data collected through mailed questionnaires for the Nurses’ Health Study were as valid as data retrieved in person. He rented an RV and held appointments with participants across the Northeast with two neurologists specializing in movement disorders. Their examination results proved a close match with the questionnaire answers.

DELVING INTO THE MYSTERIES OF NEUROLOGIC DISEASES

Early in his career, Ascherio found an interesting lead related to multiple sclerosis (MS). Women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study who regularly took a vitamin D supplement had a 40 percent lower risk of developing MS than those who did not take the supplement.

“We extended our investigation to women and men who already have MS and found that higher vitamin D levels are associated with slower disease progression, less disease activity, and clinical improvement,” Ascherio says. “Now, most people diagnosed with MS in the U.S. receive a vitamin D supplement in addition to their regular treatment.”

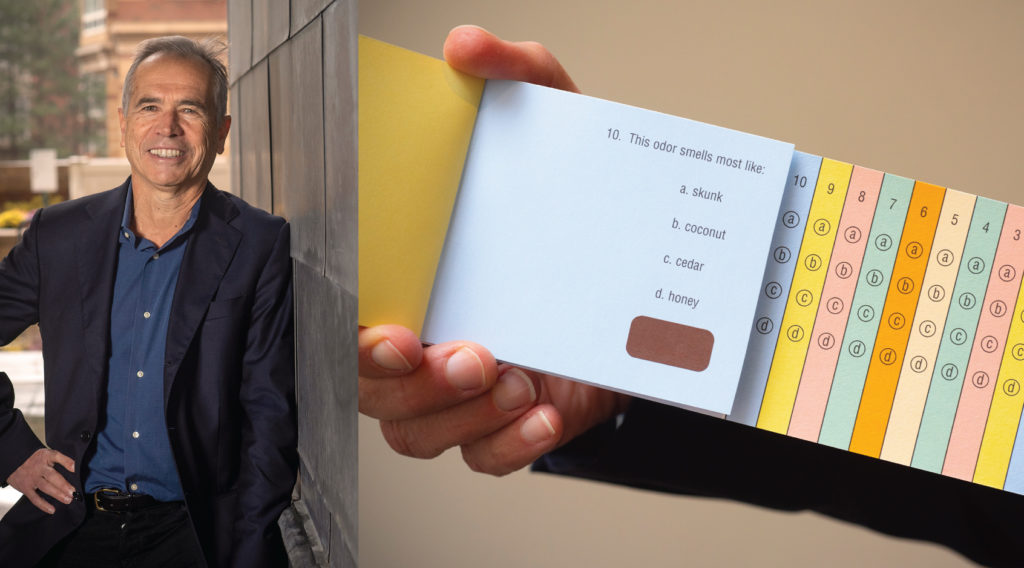

Ascherio is also examining Parkinson’s disease, which has been increasing in prevalence in recent years.

“Early signs of Parkinson’s can show up 10 years before disease symptoms appear, including reduction in sense of smell,” he says.

Using a booklet containing 10 scratch-and sniff odors, Ascherio is now screening several thousand Nurses’ Health Study participants for the disease.

DETECTING AN ELUSIVE CANCER

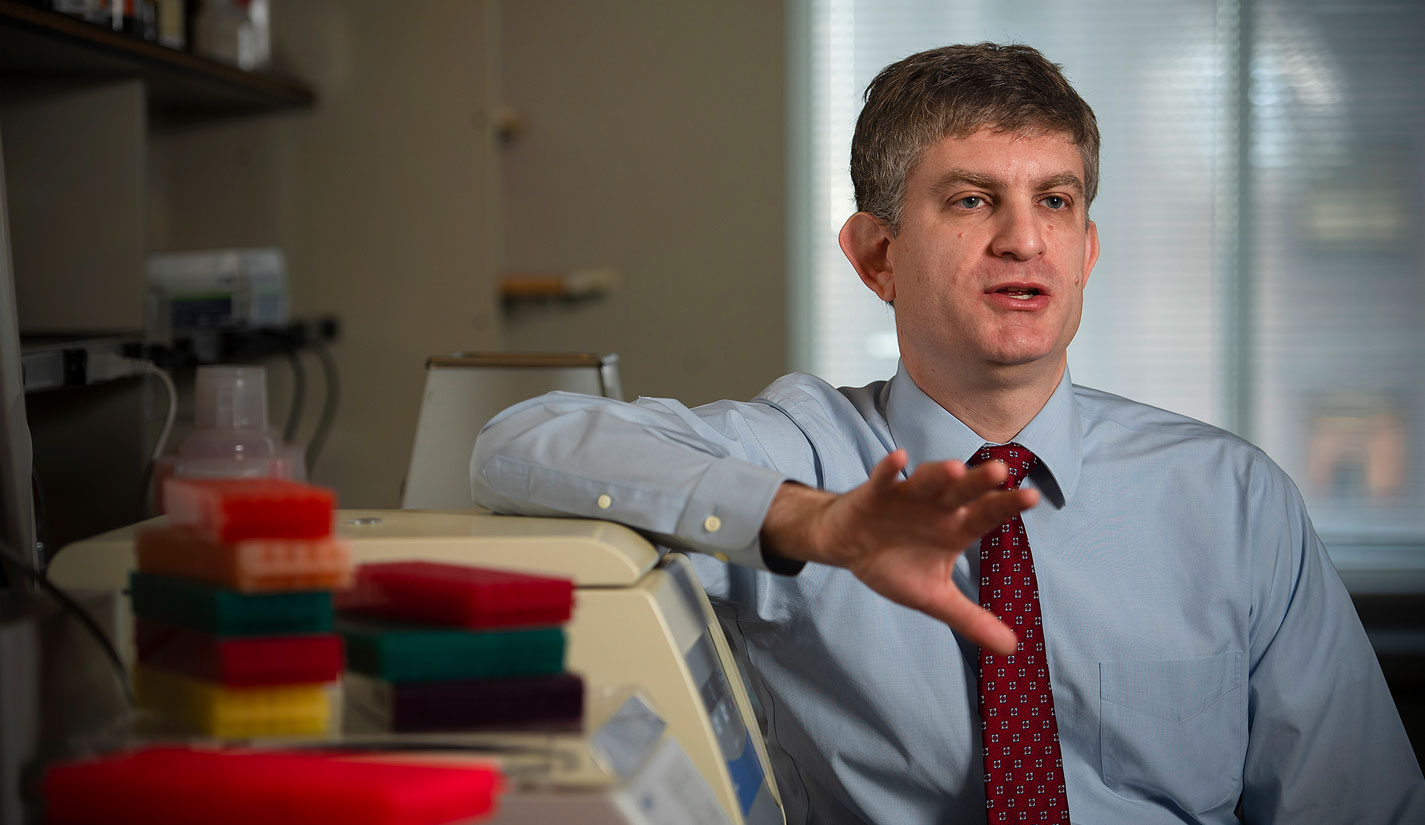

With methods ranging from low to high tech, Nurses’ Health Study investigators explore a range of complex conditions. Using a technology called metabolomics, Brian Wolpin, MD, MPH, has identified important biomarkers for early pancreatic cancer by analyzing participants’ blood samples for related metabolites—small molecules that appear in the body after breaking down food, chemicals, or tissue.

“Our job is to find markers that could ultimately go into a clinical test, much like colonoscopies screen for colon cancer,” says Wolpin, director of the Gastrointestinal Cancer Center at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center. “Early detection is desperately needed for pancreatic cancer. By the time patients come to us, the majority cannot be cured because their disease has advanced beyond the pancreas.”

Pancreatic cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death in the U.S. In 80 percent of patients the disease has already spread or metastasized by the time they are diagnosed. For the 20 percent with a small localized tumor that hasn’t metastasized, a combination of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery can lead to a cure.

“We looked at blood samples going back to the 1980s and found metabolites in the blood of people who went on to get pancreatic cancer at higher levels than people who did not develop the disease,” says Wolpin.

Early detection is desperately needed for pancreatic cancer….Our job is to find markers that could ultimately go into a clinical test, much like colonoscopies screen for colon cancer.

– Brian Wolpin, MD, MPH

Using metabolomics, Wolpin pinpointed thousands of metabolites in the blood in a single step, compared with earlier methods that could locate only a fraction of this amount. This technology, as well as genomics, which analyzes individual genes, and proteomics, which analyzes proteins, produces vast amounts of data. But these technologies are expensive.

“It’s a struggle for us because the National Institutes of Health reduced research budgets for many years,” says Grodstein. “Even funded grants often receive budget cuts, and we’d like the Nurses’ Health Study to keep growing. These big data or ‘-omics’ approaches can give us a much more sophisticated way to understand how diseases develop and how people can survive longer once they have a disease.”

PLOTTING AHEAD

As the team sets its sights on pursuing more “-omics” approaches, Grodstein and Stampfer expect to find alternate ways of preventing disease.

“As the cohort ages,” says Stampfer, “we are in a prime position to leverage our 40-plus years of data to assess determinants of healthy aging with more granularity.” Grodstein adds, “For instance, if we have metabolomic data in addition to diet, we could understand the biological effects of diet in much finer detail. When you eat better, how does that change your body? What is the biology behind this? Maybe one day we could come up with other ways, such as medications, to enhance the biological impact of a healthy diet.”

While this idea may seem far-fetched now, the future holds many possibilities.

“In 1976, when this study began, it was believed that smoking did not cause heart disease in women, only in men,” Stampfer says.

“It’s unbelievable to think of today. The Nurses’ Health Study was the first study to show that smoking is the No. 1 risk factor for heart disease and stroke in women, as it is in men.”

During its first 43 years, the Nurses’ Health Study has turned up many answers about health and longevity. The full picture is still coming into focus.