This article appeared in “Care for Every Body,” an issue that received a 2024 Gold Award for Excellence from the Group on Institutional Advancement (GIA) of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). It also received a 2024 AAMC GIA Robert G. Fenley Writing Award.]

What You Will Learn:

- Women have often been excluded from medical research other than for breast and gynecological health, meaning much medical knowledge is specific to males.

- This knowledge gap means women continue to be misdiagnosed, overlooked, and undertreated for conditions ranging from heart disease to pain to cancer.

- Brigham researchers are investigating sex-specific health differences and teaching the next generation of clinician-researchers to examine the impact of sex and gender on health.

Much of what we know about how to diagnose and treat disease is based on years of medical research that focused almost exclusively on males.

“Until recent decades, it was assumed you can study men and extrapolate that universal truth to everybody, but that doesn’t work,” says Kathryn Rexrode, MD, MPH, chief of the Division of Women’s Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. When women were included in research, she explains, “it often related to women’s breast health and gynecologic health—what some have called ‘bikini medicine.’”

Medicine and science now take a more expansive view of women’s health. But earlier approaches created knowledge gaps that continue for women across all areas of medicine, from heart disease, stroke, and diabetes to life stages including menopause.

“Everyone in medicine should care about making sure sex and gender are specifically considered in research and treatment—it’s something for all scientists and clinicians to solve,” says Hadine Joffe, MD, MSc, executive director of the Mary Horrigan Connors Center for Women’s Health, a research hub at the Brigham that investigates sex-specific knowledge of treatments and examines conditions that affect women differently than men.

Joffe says, “At a foundational level in healthcare, we know we need to think about children and elderly people differently, but the same expectation hasn’t been there for sex and gender.”

This oversight led to serious health disparities for women, including incorrect diagnoses, lost opportunities for treatment, and wrong doses of medications. To make care more equitable, Joffe, Rexrode, and hundreds of others at the Brigham are pushing forward research, training, and care looking explicitly at the impact of sex and gender on health. Through their example, they’re encouraging new generations of clinician-researchers and developing knowledge to benefit everybody.

Until recent decades, it was assumed you can study men and extrapolate that universal truth to everybody, but that doesn’t work.

Kathryn Rexrode, MD, MPH

The nation’s No. 1 killer: not ‘A MAN’S DISEASE’

Cardiovascular disease has been the No. 1 killer for decades nationwide. In the 1980s, the number of men dying from it began decreasing steadily as research in men discovered better ways to manage the disease. At the same time, the medical community assumed women were mostly protected from the disease by hormones, namely estrogen.

However, as men’s death rates declined from cardiovascular disease, women’s death rates rose. In 2000, approximately 500,000 women died of the disease nationwide, compared with 440,000 men. This awareness led to public health campaigns and research including women, leading to a 21% drop in women dying from the condition by 2010.

Despite emerging evidence that cardiovascular disease looks different in women compared to men, women with the disease are still misdiagnosed, overlooked, and often undertreated, notes JoAnn Manson, MD, MPH, DrPH, chief of the Brigham’s Division of Preventive Medicine, scientific advisor of the Connors Center, and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health at Harvard Medical School (HMS).

“Major knowledge gaps remain,” says Manson. Compounding the problem, she says, “is the lingering misconception even among the public that heart disease is a man’s disease. It’s extremely difficult to dispel long-held notions.”

Persisting against disparities

An innovator and a role model for many, Manson has led landmark studies for more than 30 years that continue to add new knowledge on a range of diseases in women. Yet she and other scientists at all stages of their careers voice frustration at continued roadblocks in research and health disparities.

“Many studies today are still not large enough to look rigorously at sex differences and come up with actual recommendations that might differ by sex or gender,” says Manson, expressing dismay. “There’s more attention to sex differences now than before,” she concedes, “but limited research funding is a problem.”

Training the next generation is one way to address the issue, says Joffe, who is the Paula A. Johnson Professor of Psychiatry in the Field of Women’s Health at HMS. She cites a two-year educational opportunity through the Connors Center called the First.In.Women fellowship. Xiaowen “Wendy” Wang, MD, is one of two fellows focusing on women’s health and cardiovascular disease.

“Women often experience implicit bias,” says Wang. “They’re less likely to be put on medications known to reduce death after a heart attack or to get certain procedures after a heart attack. A lot of studies show women with symptoms of heart disease are still not always taken seriously when they go to a hospital.”

As Wang builds skills to evaluate and understand sex differences through the fellowship, she is already making an impact in research to improve treatment options for women.

Unsteady, yet gaining ground

Research regulations have influenced change. Thirty years ago, Congress passed the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act, mandating that women and people of color be included in NIH-funded clinical research to assess new treatments, devices, and procedures.

“With huge progress in regulations,” Joffe says, “there’s more conversation and expectation for scientists to study males and females and ask if results vary by sex and gender.”

But much like retrofitting a heating system in an inadequately insulated house, unintended issues can arise in study design. For example, Rexrode notes, a trial of a drug for people with cardiovascular disease may cap the age limit at 70 for logistical reasons, but this could inadvertently exclude many women since they tend to develop the disease later in life than men.

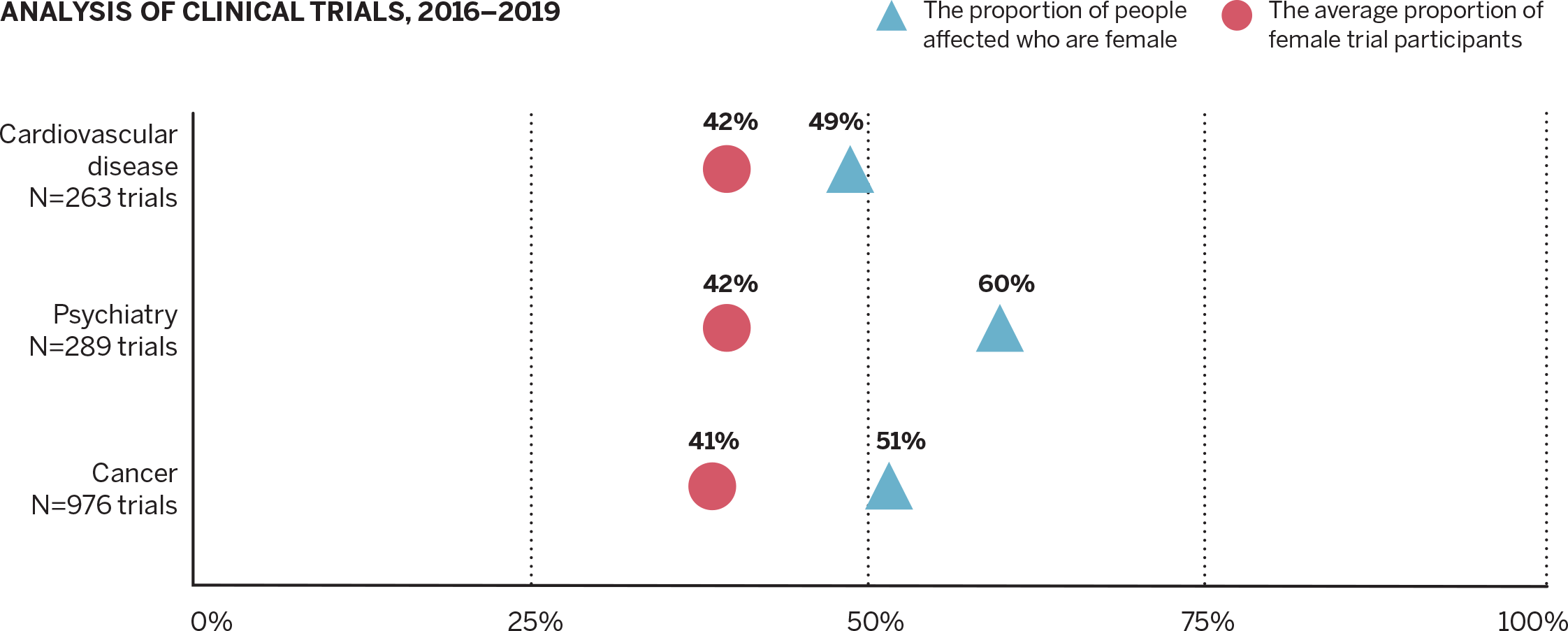

In fact, when Connors Center scientists analyzed 1,433 clinical trials conducted nationwide between 2016 and 2019, they discovered women remain underrepresented in trials for many health conditions.

Until recently, female animals, tissues, and cells were also largely excluded from preclinical studies, which take place before a treatment is tested in people. The Connors Center advocated for policies to change this on a national level and helped inspire the NIH to issue a requirement in 2016 that researchers include sex as a biological variable in preclinical studies.

Major knowledge gaps remain. [There] is the lingering misconception even among the public that heart disease is a man’s disease.

JoAnn Manson, MD, MPH, DrPH

Safer, more effective treatments

Seizing on this momentum, Joffe and her colleagues started the First.In.Women Precision Medicine Platform at the Brigham to help ensure women are considered when new drugs and devices are developed. To finance this work and draw attention to it, the Connors Center builds and cultivates relationships with philanthropists, foundations, venture capitalists, and the biopharmaceutical community.

“There are real consequences here,” Joffe says. “If you roll out a new treatment and haven’t tested it in the population that will be using it, there could be more side effects. And we’ve seen that women of every age, young and old, have more side effects from medicines than men do.”

The sleep aid drug Ambien offers a striking example. For 20 years, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) received reports of severe drowsiness the morning after people took the medication. For some individuals, mostly women, the impairment led to car accidents and other dangers. In 2013, the FDA cut the recommended dosage of Ambien and related sleep medicines in half for women because of differences in how they metabolize the drug.

“An FDA-approved difference in dosing for women versus men is not the case with most medications, but probably should be for several medications in addition to sleep medicines,” says Manson. For example, she says, thrombolytic drugs have posed problems. They help break up blood clots, but women are more susceptible to bleeding. In addition, women report muscle aches with cholesterol-lowering statin drugs more often than men and are more susceptible to irregular heart rhythms on certain medications.

Joffe notes that when women are considered throughout the research process, safety can be improved, and so can overall effectiveness and precision. “We have an opportunity to develop new diagnostics and therapeutics beneficial to everyone,” she says.

Women Still Trail Men in Clinical Trials

Connors Center scientists analyzed 1,433 clinical trials between 2016 and 2019, finding 41.2% of the 302,664 participants were female. Females were underrepresented in each of the three disease areas evaluated, meaning a lower proportion of females were studied than those expected to use the drugs or devices tested.

Source: Contemporary Clinical Trials journal, April 2022

Tailoring care for women

Caring for women more precisely based on the latest research is the premise of the Brigham’s Gretchen S. and Edward A. Fish Center for Women’s Health. With more than 40,000 patient visits each year, the center offers primary care and 14 specialties that focus on conditions with higher risk and prevalence in women, as well as conditions traditionally undertreated in women.

“It’s unusual to have this kind of care integrated and all in one place,” says Rexrode, whose division oversees its clinical operations. “That’s the gift of the Fish Center.”

Eve Rittenberg, MD, whose Brigham career spans three decades, is a leading primary care provider at the center. She and her colleagues treat many conditions, but every week, they hear a similar story: Patients share they recently started menopause and are having trouble sleeping.

“It’s important for providers to understand the biologic component of a patient’s sleep disruptions and the possible treatments,” Rittenberg says. “It’s also important to understand any gender-specific aspects of her symptoms. I may learn she works outside the home and is also the primary caregiver for her children and aging parents.”

Rittenberg uses this information to suggest a treatment plan. At times, patients need more in-depth care, so she refers them to specialty care at the center, such as endocrinology or medical social work.

“Having a wide range of specialists right here helps us offer comprehensive care for women,” she says.

To address growing demand from patients, the center added two new services between 2019 and 2020: a sleep specialist and a Menopause and Midlife Clinic.

Expertise for a highly unmet need

“Menopause and midlife have been a neglected part of clinical care,” explains Rexrode, noting few providers nationwide specialize in this area. “But every woman who lives long enough goes through menopause. Nearly 75% of women experience symptoms that last 5 to 7 years on average. That’s why we started this clinic.”

With a yearlong wait list of patients from the Boston area and out of state, the need for specialized menopause care is overwhelming. As a result, the practice is working to expand.

“Menopause is not just what people classically think of as hot flashes and night sweats, but can commonly lead to sexual dysfunction, brain fog, weight gain, cardiovascular ramifications, and more,” says Tara Iyer, MD, NCMP, lead physician of the Menopause and Midlife Clinic.

Menopause usually happens between ages 45 and 55 when the ovaries stop making estrogen and other hormones, causing menstrual periods to end. “Women don’t age the same way as men because they lose those hormones; there is a distinct difference,” Iyer says.

Erin Duralde, MD, a physician who completed fellowship training in the clinic, says, “Sometimes our patients are at their wit’s end because they’ve been struggling with symptoms and not been able to find a clinician who understands the many manifestations of this life phase and how to address them.”

Since menopause is given little—if any—attention in medical school and residency training, providers lack knowledge in counseling patients and providing appropriate treatments.

“Why don’t we learn about this in standard medical training?” Duralde says. “It sends the message that women don’t matter, and that the changes and symptoms of menopause aren’t something to ask about or improve. Meanwhile, there’s a lot of good we can do to improve women’s health during this major life transition.”

Our patients are extremely grateful. We hear comments like, ‘This changed my life almost overnight,’ ‘Finally, I can sleep,’ ‘I feel like myself again.’

Tara Iyer, MD, NCMP

Drawing on their training and knowledge, Iyer and Duralde help relieve patients’ symptoms with menopausal hormone therapy (HT) and non-hormonal treatments.

In the past, HT received a negative reputation that continues to cloud public opinion today. Just over 20 years ago, a large-scale study of women ages 50 to 79 called the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) included a clinical trial for HT, which discovered the treatment did not help prevent cardiovascular disease as was hypothesized. In fact, the study found that health risks of the treatment outweighed the benefits for women overall when used for chronic disease prevention.

However, Manson, one of the principal investigators of the WHI and past president of the North American Menopause Society, conducted several follow-up studies examining age and risk factors that found HT is effective and safe for most women under age 60. In the past decade, with evidence from these and other studies, multiple medical societies have endorsed use of HT for treatment of menopause symptoms and recommended against its use for prevention of cardiovascular disease.

Iyer sees it as her mission to educate each patient on the latest recommendations and work with them on individualized treatment plans.

“Our patients are extremely grateful,” Iyer says. “We hear comments like, ‘This changed my life almost overnight,’ ‘Finally, I can sleep,’ ‘I feel like myself again.’”

Beyond what can be life-altering day-to-day symptoms, menopause dramatically escalates women’s risk for developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, and some cancers.

To help providers understand the full picture, Iyer teaches medical students and residents, and recently presented to colleagues at the Fish Center’s monthly continuing medical education talks.

“By teaching about knowledge gaps, I hope to make a big impact locally and, in the longer run, nationally,” she says. “There are new treatments on the horizon, and it’s exciting being part of this work.”

New questions » new knowledge

At the Connors Center, researchers are also looking at the effects of menopause on health. Joffe, past president of the North American Menopause Society, recently concluded a 5-year study funded by the NIH on how sleep problems affect metabolism and risk factors for heart disease during and after menopause.

“Everyone thought women gain body fat because estrogen levels go down,” Joffe says. “That’s true, and we’re showing for the first time that sleep disruptions also contribute to body fat accumulation.”

The study recruited women under age 45 to come to a sleep lab where their sleep was interrupted repeatedly by a loud alarm throughout the night for three nights, and timed when their estrogen levels were high. Then they brought the women back for a repeat study after temporarily lowering their estrogen levels to mimic menopause. After the second test, the researchers saw rapid increases in participants’ triglyceride and LDL cholesterol levels.

“In both instances, we found the body shifted how it breaks down fuel and burned less fat, which means you would likely gain weight unless you change your diet,” says Leilah Grant, PhD, an investigator in the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders who worked with Joffe on the study.

Shadab Rahman, PhD, a lead investigator in sleep and circadian disorders and collaborator on the project, conducted a small separate study of men to examine sex differences in sleep interruption. He found that for men, sleep disruption decreases appetite hormone levels tied to feelings of fullness, which could lead to more eating and weight gain. In the main study, researchers found that women with low estrogen were affected in the same way as men.

“In the sleep field, we’ve traditionally focused on how many total hours you sleep,” Rahman says. “Our study shows that even with the recommended 7.5 to 8 hours of overall sleep time, repeated waking during the night caused immediate detrimental effects on metabolic health in women and men.”

Because of menopause, Joffe explains, women’s likelihood of being naturally awakened in the night increases. “In menopause, 80% of women experience hot flashes and 50% experience a pattern of sleep interruption,” she says.

The good news is that nighttime wakeups can be minimized through behavioral sleep therapy, better sleep routines, and medications.

“Fragmented sleep might ultimately be bad for heart health,” Joffe says. “People don’t realize it’s a problem to be up multiple times a night and figure they can sleep in to compensate. There’s a particularly important public health message here for women: Make sure your sleep is as continuous as possible.”

Knowledge improves health

Studies like this provoke more questions, inspire further research, and inform care and training.

Cardiologist Jennifer Jarbeau, MD, uses everything she knows about sex and gender differences in caring for patients and educating residents and students. During patient visits one morning at the Fish Center, Jarbeau proved part detective and part coach as she poured over medical records before each visit and talked with patients. This day, an internal medicine resident shadowed her.

After examining one patient in her 80s with atrial fibrillation, an irregular heart rhythm, Jarbeau decided to adjust the patient’s medications. Back in the physicians’ workroom, she walked the resident through appropriate medication choices based on a patient’s age, sex, and body size. She advised avoiding one medication altogether because older women tend to have toxic reactions to it.

The morning continued like this with patient visits, where Jarbeau counseled patients on diet, exercise, and treatment regimens, along with teaching the resident about cardiovascular tests, female-specific risk factors, sex differences in symptoms, and more.

“I enjoy teaching physicians and patients,” says Jarbeau, a past president of the American Heart Association of Southern New England. “We need to keep raising awareness and make women feel heard, treat them, and get them healthier.”

We need to keep asking questions and encouraging new ways of thinking. At the Brigham, we’re here with advocacy and evidence to raise awareness and improve care.

Hadine Joffe, MD, MSc

Balancing the scales

“Even in 2023, we’re still playing catchup with women’s health,” Rexrode says. “To do well-designed research powerful enough to examine sex differences and provide evidence-based health recommendations differing by sex, we need much larger studies.”

Manson explains, “It can require four times the sample size to do a rigorous test of sex differences. There are many researchers who want to further knowledge in this area, but the reality is that the funding climate for this research is challenging.”

Balancing the scales to give all patients evidence-based care takes a gargantuan effort, and Brigham clinician-scientists have seen their efforts making a difference.

Joffe recalls physicians at academic meetings saying her studies helped them care for patients differently. “Patients ask us questions like, ‘Why did this happen?’ or, ‘What’s known about this for me?’—and we can answer those questions if we collect and report certain data,” she says.

“During my psychiatry training in the 1990s, I asked questions like, ‘Why do women have sleep problems or depression after having their ovaries removed?’ and I’d receive the response, ‘We’ve never heard anybody ask that before,’” Joffe says. “Our understanding of biology has advanced tremendously over the past 20 to 30 years. We need to keep asking questions and encouraging new ways of thinking. At the Brigham, we’re here with advocacy and evidence to raise awareness and improve care.”