Every day and everywhere, people depend on electronic devices to manage the most personal aspects of their lives—including their health. The gadgets vary from smartphones and fitness trackers to futuristic implantable devices, and even smart tattoos that send data from the skin’s surface. Digital health tools at home and on the go are redefining healthcare, from how information about health and well-being is collected and shared, to helping people take steps toward healthier lives, to increasing convenience and cost savings for patients, providers, and entire health systems.

Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) is a hive of invention and discovery, abuzz with innovators building, testing, and deploying evidence-based, user-friendly technologies to improve patients’ lives. Here are three examples of digital health tools in use at BWH that are making healthcare smarter—and more compassionate.

HOME SCREEN

One night after dinner at home, Bill Terry, MD, suddenly felt cold and began shivering uncontrollably. Living a short distance from BWH, where he works as an administrator, Terry quickly drove himself to the Emergency Department (ED). In the ED, Terry was preliminarily diagnosed with a chest infection and admitted, but he never made it to an inpatient room. Instead, he returned home accompanied by a young doctor, David M. Levine, MD, MPH, toting a backpack full of medical supplies.

The beauty of what Dr. Levine has done is that the apps are intuitive to use, and they enable an immediate response from the care team.

— Bill Terry, MD

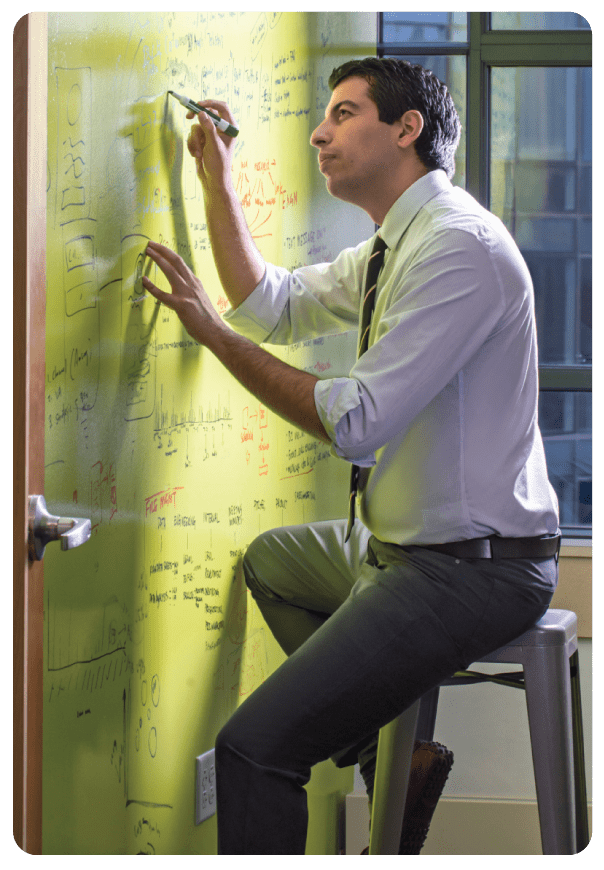

A physician and researcher in BWH’s Division of General Internal Medicine and Primary Care, Levine runs a program called the Home Hospital. With a wireless monitoring system and other portable medical equipment, Levine can convert any home into an inpatient room—minus the inconvenience, higher costs, and added stress of hospitalization.

Because the symptoms of Terry’s infection were manageable and his apartment was near enough to the hospital in case he needed quick assistance, he was invited to participate in the project. Terry immediately opted in.

“It was a no-brainer,” says Terry, who had never used a digital health device before. “I knew that being at home in my own bed would permit a quality of care and comfort level not even the best institution could match.”

He adds, “I was confident in Levine, and professionally speaking, I was intrigued by the idea of helping him chip away at the high cost of healthcare.”

At Terry’s apartment, Levine started him on an IV and attached a patch to Terry’s chest that wirelessly sent his vitals to an app on a tablet computer (short for “application,” an app is a program that can be downloaded to a mobile device). The tablet also served as Terry’s call button, alerting nurses and Levine in case he needed attention.

The first test of the system came before dawn the next morning, when Terry noticed a large red welt on his leg. Levine was there within an hour to assess. After determining it was cellulitis, Levine set Terry up with a device that automatically delivered antibiotics throughout the day.

“The beauty of what Dr. Levine has done is that the apps are intuitive to use, and they enable an immediate response from the care team,” Terry says. “For a model like this to work, you need care providers like him who are as responsible and comfortable with delivering care remotely as they are in a hospital.”

Terry was discharged from the program after five days. “It was such a family-friendly experience, being in my own home and having my wife with me the whole time,” he says. Since the pilot, the Home Hospital team has cared for more than 100 patients. The results of the initial project, recently published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, showed up to 50 percent reductions in cost over traditional hospitalization and improved quality of experience for both patients and care providers.

“Our Home Hospital team works incredibly hard, and our time is rewarded with great clinical, population health, and patient experience outcomes,” says Levine. “It’s been so refreshing to work with patients on their terms, in their homes and with their families.”

BE KIND, REMIND

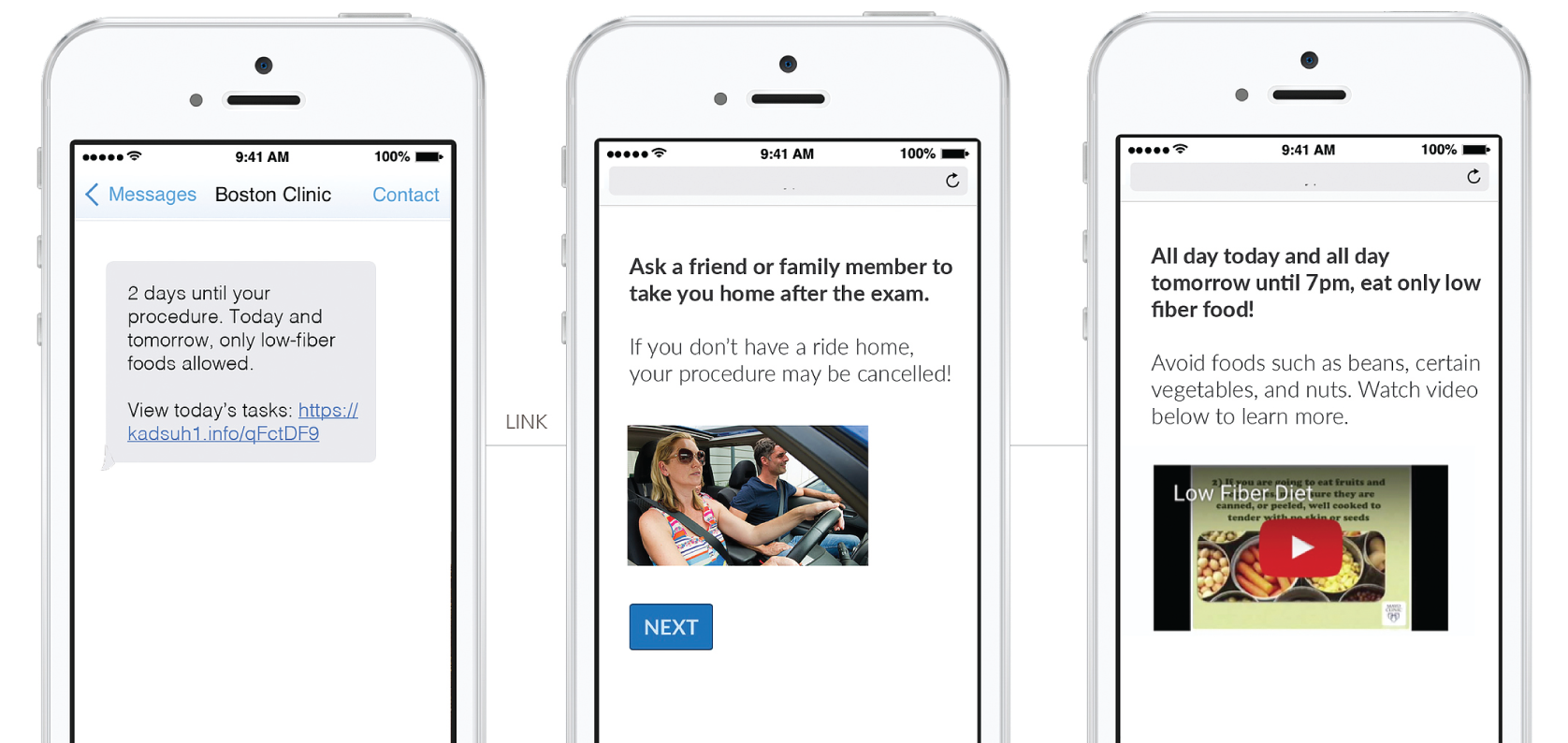

Preparing for a colonoscopy can be an ordeal, with strict dietary restrictions and an unpleasant, bowel-cleansing drink that clears the digestive tract so the gastroenterologist can get a complete view. Indeed, the preparation is so dreaded that one in five people who get a colonoscopy must repeat the procedure because their intestinal tract isn’t sufficiently cleared.

Seeing this preventable situation derail care for patients bothered Omar Badri, MD, an internal medicine and dermatology resident at BWH.

“It was hard for me to understand why patients often didn’t have the information they needed, when they needed it, to make the right choices before their colonoscopy,” Badri says. “I learned it doesn’t work for doctors to give patients a 30-second talk using medical jargon or a piece of paper that is easily lost, and then expect them to be ready a month or two later for their procedure.”

He thought of all the messages he receives on his phone every day, from meeting reminders to notifications that his coffee order is ready. He wondered if patients’ smartphones could help improve outcomes by providing clear information at each stage of their preparation.

We found that Medumo users had a huge reduction in no-shows and cancellations, and improved performance with the colonoscopy procedures. It just took off.

— Omar Badri, MD

Badri and his collaborators created a HIPAA-compliant reminder service called Medumo, which sends timely emails and text messages to let patients know how to prepare for a colonoscopy, preoperative anesthesia evaluations, joint replacement surgery, and other procedures. Since its launch last year, Medumo has been adopted by 17 hospitals in the United States and will send millions of messages to more than 400,000 patients this year.

“Nearly everyone today uses their phone as a gateway to communicating with the world,” he says. “We found that Medumo users had a huge reduction in no-shows and cancellations, and improved performance with the colonoscopy procedures because inadequate preparation was reduced by up to 67 percent. It just took off.”

Claudette Traver was the ideal candidate for Medumo. Before her first colonoscopy, she forgot many of the instructions she’d received in the clinic, tried piecing together the correct information on her own, and then learned she would need to redo the procedure because of incomplete preparation. Medumo transformed Traver’s preparation for her follow-up colonoscopy.

“All I had to do was read the texts,” says Traver. “I wasn’t second-guessing myself, because the reminders came right when I needed them. In the follow-up procedure, they were able to remove 19 nonmalignant polyps—because I was well informed and ready from the start.”

CLOSE COMPANION

Jonathan Potter is skeptical of health apps and their claims to transform people’s wellness. However, after he was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), he was willing to try almost anything to feel better. In a PTSD patient group he joined at BWH Advanced Primary Care Associates at South Huntington, Potter learned about an app called Cogito Companion. For a health app, it has unconventional origins: its machine learning algorithms and advanced voice analysis were developed for customer service centers, intended to help agents gauge callers’ attitudes on the phone and then suggest techniques to improve their satisfaction with the conversation. Like an ultra-precise mood detector, the program is so attuned to unconscious, nonverbal signals like tempo, emphasis, and mimicry, the software’s developers couldn’t act upset and fool it into sensing true distress.

Having sophisticated, built-in sensors in our pockets creates opportunities for observing how we live that didn’t exist 10 years ago.

— David K. Ahern, PhD

Researchers at BWH were intrigued to see if Cogito’s real-time emotional intelligence and empathy might help people living with depression and other conditions. The team worked with developers at Cogito to pair the Companion software with sensors built into smartphones. As patients speak into their phones or move through the

day, the app analyzes patterns in their speech and activity to keep track of their emotional well-being. The data gives clinicians a chance to respond sooner to warning signs and have richer conversations with patients.

Potter was an early user of the Companion smartphone app. On his daily walks with his dog, Beau, he recorded his thoughts in the app. Hoping to get a good report, Potter tried his best to sound upbeat. After one recording, he was stunned when Companion sent him an alert that he sounded down.

“I knew how Companion was supposed to work, but I didn’t believe it actually worked until I saw the way it was interpreting my messages,” says Potter. “It was listening to how I expressed my thoughts, not the actual words I was saying. It was like talking to a friend who really cared about how I was doing, someone who would call me on saying I’m fine when I’m obviously not.”

David K. Ahern, PhD, led the Cogito Companion study at BWH and directs the Behavioral Informatics and eHealth program with the Department of Psychiatry. Because of the insights they shed on patients’ behavior patterns, he says apps like Companion could change the paradigm for monitoring mental health conditions.

“Having sophisticated, built-in sensors in our pockets creates opportunities for observing and understanding how we live that didn’t exist 10 years ago,” says Ahern. “What providers do with that information could be an even bigger change. That will require us to move toward a population health strategy—not just filling out surveys at appointments and waiting to see how patients are doing, but actually following them in real time and knowing when their care needs to escalate.”

At home, Potter says the app calls out concerning behavior with a level of objectivity and clarity that could be especially helpful for people who are struggling.

“I’m lucky to have people in my life who care about me and how I’m doing, but others might not, or they might not want to talk openly about their mental health,” he adds. “In that way, this app could really help people feel less alone and get the help they need.”

CHARGING ON

The best of what’s to come with digital health may be its power to extend the reach of healthcare. Actions and conversations that used to occur only in an exam room can now happen anywhere.

“Having Companion on my phone gave me the self-awareness to challenge negative thoughts in the moment,” says Potter. “The next time I saw my doctor, the log gave us a place to start our conversation so that I could get the most benefit from my appointments.”

Integrating wearables and devices into routine care will take time, since they don’t fit traditional healthcare delivery models.

“Wearables and apps fit healthcare models of the future: population health, precision medicine, and personalized care,” Ahern says. “Systems will need to evolve to enable care delivery with these devices without compromising privacy—and we’re seeing that evolution now.”

In the meantime, Ahern, Badri, and Levine are excited to see early glimpses of how thoughtfully developed tools can streamline the business of healthcare and help make patients happier and healthier.

“Using Medumo for colonoscopy preparation helps endoscopists get a better visual of the colon and find adenomas,” Badri says. “That’s a huge outcome. Finding cancer early is why we screen in the first place!”

The tricky work ahead will be to address the massive, unregulated field of products available to consumers, and helping patients separate the clinical usefulness from hype.

“I’m usually the ‘Debbie Downer’ at digital health conferences, warning people that many apps lack evidence and some are shown to have a negative impact,” says Levine. “Physicians don’t prescribe just any old pill. They have to make sure that pill works. We need the same careful, evidence-based mindset with apps and wearables. It’s still part of doing no harm.”