[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in 2016 and was last updated in 2019.]

TREATMENT | TRAGEDY

All it took was a small dose. A car accident landed John* in an emergency room, where he received a short-term prescription of 20 to 40 milligrams per day of Percocet pain medication.

“I liked the feeling it gave me,” John says. “I was depressed, and it filled something missing inside me. I started getting pills on the street and took them all day every day. One in the morning, one at 10, one at 12, one at 3. I was probably taking 300 milligrams a day by the end. I didn’t think anything of it because I had great jobs and friends, dressed nicely, had a car. I was duped into believing my life was ok.”

When his daughter was born several years later, John tried to cut back. But he couldn’t.

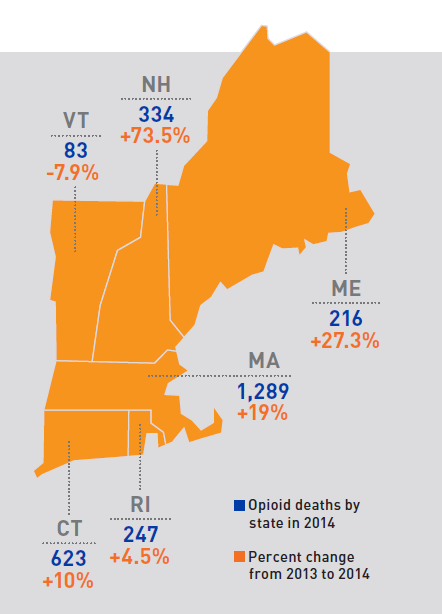

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

A ‘perfect storm’

Addiction to opioids is wreaking havoc on families and communities across the United States, with overdoses from prescription pain relievers and heroin causing a surge in hospital visits and fatalities. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 28,647 people died from overdoses in this country in 2014, quadruple the rate in 2000. Massachusetts has one of the fastest growing overdose death rates, increasing 18.8 percent from 2013 to 2014.

While these statistics have dominated headlines, the root problem is these drugs are frequently prescribed and readily available, says James Rathmell, MD, chair of Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“To a certain extent, the ‘House of Medicine’ has created this problem because we want to take good care of our patients,” Rathmell says. “At the center, you have a patient in pain. You have a tool that works. Do you deny them?”

The quandary medical professionals find themselves in started decades ago, explains Martin Samuels, MD, director of the Program in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience. Nearly 30 years ago, as the medical profession began to recognize chronic pain as an increasing concern, two pain specialists in New York co-authored a paper stating that opioid medications could be used safely and effectively for all patients with chronic pain, based on a limited study of 38 patients.

“It was the perfect storm,” Samuels says. “A major anti-pain movement introduced pain as the fifth vital sign, and we began to ask patients to rate their pain on a scale of 0 to 10. There was, and still is, huge pressure on doctors to prescribe opioids.”

Seizing on the opportunity, pharmaceutical companies developed new pain medications with exaggerated claims of being non-addictive, he adds. For a small percentage of the population, the pills alone can get people hooked. Making matters worse, early formulations of medications like Oxycontin could be crushed to be snorted or injected.

Today, several studies show the amount of pain reported by Americans has not decreased overall even though medication sales nearly quadrupled from 1999 to 2014 (mirroring the rise in overdose deaths). The amount of misuse, however, has been on the rise, with those seeking pills for non-medical use getting them most often from friends or relatives.

As opioid pills became more available, so did their more potent cousin, heroin. With a sharp rise in smuggling across the U.S. border with Mexico, the drug has become cheaper and easier to obtain.

Indeed, when money got too tight for John to buy more pills, a friend suggested heroin. “Worst mistake I ever made,” he says.

“The safety zone for heroin is much smaller than for prescribed oral medications,” Samuels says. Heroin’s initial effects are shrinking pupils, altered thinking, and increased happiness. “If you overdose, the heartbeat will weaken, you’ll breathe less deeply. Eventually, you stop breathing altogether.”

John has overdosed more than once. In the summer of 2015, it took large amounts of Narcan—an opiate antidote—to bring him back to life.

Determined spirit

Scott Weiner, MD, MPH, emergency physician at the Brigham, has seen the opioid crisis unfold before his eyes.

“We did everything we could for a patient who recently overdosed on heroin, but he was gone,” Weiner says. “At 3:00 in the morning, I had the task of calling his parents. I want to do whatever I can to prevent this.”

He also wants to put the brakes on doctor shopping and prescription medications being sold on the street. One tool Weiner uses is the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, a database listing opioid prescriptions for patients across Massachusetts. But slow reporting times have limited its effectiveness.

“You could go to one hospital a day for a week and doctors wouldn’t see prescriptions from those visits,” Weiner says.

Through his role on the board of the Massachusetts College of Emergency Physicians, Weiner is advising the state on a new version of the database set to release this summer. On his home turf, he is working to integrate the database with eCare, the hospitals’ electronic medical record system.

This fall, physicians will be required by law to check the database before prescribing a schedule 2 or 3 narcotic, one of many provisions in an opioid bill passed in March in Massachusetts.

While most patients who receive a short-term pain reliever do not ultimately become addicted, Weiner says, “We owe it to our patients to screen them before prescribing these medications and counsel them on the risks and benefits.”

Barriers to treatment

After his near-fatal overdose, John reached out to the Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital outpatient Suboxone Clinic and began medication-assisted treatment, a combination of counseling and the medication suboxone, part opioid to ease withdrawal symptoms and part naloxone to fight the full effects of the opioid.

“I hope not to wake up every morning and take a medication, but if the alternatives are that or be dead in a car on the highway, I choose the medication,” John says.

“Addiction is a public health issue,” says Joji Suzuki, MD, director of the Division of Addiction Psychiatry at the Brigham. “It’s not like an infection you clear, but a chronic disease like diabetes or obesity that requires care over a long period. It’s a very treatable illness.”

“The demand for help is never-ending,” he adds. “Right now, we’re at capacity with 100 patients, and there’s a two- to three-week waiting list.”

Suzuki is expanding his team, as well as working to move addiction treatment beyond the clinic and into general medical settings.

“Offering this lifesaving treatment where patients are most comfortable dramatically reduces stigma,” Suzuki says, describing a medication-assisted program he oversees at one of BWH’s primary care clinics. “Patients are often ashamed to seek help from addiction specialists or psychiatrists.”

Creating a roadmap

There is a severe shortage of addiction treatment options throughout Massachusetts and across the country. In 2018, Congress committed $6 billion in new funding for programs to combat the opioid crisis through 2020, and state governments are dedicating more resources to expand access to treatment.

With Suzuki’s leadership, BWH is one of the few hospitals in the country to begin suboxone treatment in hospitalized patients. Suzuki’s team has also published studies showing the benefits of longer, shared medical appointments that bring multiple patients together with a team of healthcare providers, a model used exclusively by BWFH’s suboxone clinic. In 2016, the team began offering shared medical appointments through video conferencing with a Cape Cod primary care clinic.

The hospitals are also working on the frontlines of pain management and addiction prevention. For example, the Department of Nursing created an educational handout for patients on how to use opioid medications safely and dispose of leftover pills.

“Many impassioned people are doing great work, but it’s been fairly siloed,” Weiner explains. “As an institution, we have the opportunity to come together and be a leader for change.”

Across the Brigham, Weiner is leading a comprehensive effort to develop a uniform approach to manage acute and chronic pain, as well as addiction prevention and treatment. Employees from many disciplines—primary care, nursing, pain, psychiatry, emergency medicine, pharmacy, and more—as well as patients, are providing input to develop prescribing guidelines, screening tools, and training and decision support for clinicians.

“Everything is on the table,” says Rathmell. “Should patients be on opioid medications? If so, who? What should the doses be? Who is susceptible to addiction? How do we wean patients on high doses for chronic pain?”

Rathmell’s department runs the Center for Pain Medicine, which sees many patients dealing with chronic pain. Bob*, one of the center’s patients, relies on opioid medications to cope with long-term pain in his back, knee, and other areas of his body. “Before I came to the pain center, I was always worried if I was doing the right thing,” Bob says. “If I had four pills for the day but the pain was still really bad, I wondered if I should take a fifth one.”

With guidance from his pain physician, he switched medications and has successfully reduced his dosage. While he is still limited physically, the regimen makes a big difference in his quality of life.

“The opioid crisis is an epidemic, but we can’t forget there are people like me who benefit from the medication,” Bob says.

A path toward change

Meanwhile, John is finding his way to sobriety. He has lost several family members to drug and alcohol addiction, and has relapsed in the past with shorter treatment programs.

“I have dreamed of being able to get through the day without blowing all my money or wasting my time seeking out a drug, and being controlled by it,” he says. “The people at the clinic have treated me with such respect and given me the support I’ve needed. For the first time in my life, I feel good. I don’t feel like I need anything.”

Setting up systems to help patients like John avoid addiction and patients like Bob manage their pain appropriately requires comprehensive change, Weiner notes. He and clinicians across the institution are conducting research and getting involved at the local and national levels. Suzuki is developing training for primary care physicians to increase their understanding of addiction treatment, as well as a telephone line offering clinicians real-time consultations. Weiner, Somerville, and others have testified at the Massachusetts State House for legislation on opioids. Rathmell recently contributed to the National Pain Strategy, an action plan for improving pain management coordinated by the National Institutes of Health.

“Together, we’re working to inform policymakers and state agencies to solve this crisis, while developing solutions we can implement at the hospitals,” Weiner says. “Opioid-related harm is the public health issue of this time. We at the Brigham must lead and take on this challenge.”

*The patients’ names have been changed to protect their privacy.

SAFEGUARD AND DISPOSE OF OPIOID MEDICATIONS

Bob* keeps his morphine in a safe to prevent his children and anyone else from accessing it. A patient of BWH’s Pain Management Center, he is one of an estimated 100 million American adults affected by chronic pain.

“If you have a gun in the house, you should keep it locked up,” Bob says. “Same thing with medication like this.”

Nurse educators developed a handout on the safe use of opioids, urging patients to secure their medications and properly dispose of leftover or expired pills.

How to dispose of your medications

- At BWH: Drop off in the receptacles at the outpatient pharmacy at 45 Francis Street, Boston (M–F, 9 a.m. -5:30 p.m.) and the outpatient pharmacy located at 850 Boylston St., Chestnut Hill (M-F, 9 a.m. -4 p.m.)

- Police: Call your local police station and ask if a drug take-back box is available.

- DEA ’s National Drug Take-Back events: Visit www.dea.gov or call 800-882-9539 for collection site information.

- Learn more online: Visit www.fda.gov and type these keywords in the website’s search area: medication disposal.

*The patient’s last name has been withheld to protect his privacy.