Between 1955 and 1994, state-run psychiatric hospitals across the country discharged most of their patients in a social experiment called deinstitutionalization. It coincided with three factors: greater availability of effective psychiatric medications, the creation of Medicaid and Medicare, and a societal movement toward treating people in their communities instead of institutions.

Despite positive intentions, deinstitutionalization helped fuel a new crisis: mass incarceration. Jhilam Biswas, MD, a forensic psychiatrist who directs the Brigham’s Psychiatry, Law, and Society Program, says nearly 50% of the nation’s prison population suffers from mental illnesses.2 In fact, jails in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago are now the three largest psychiatric institutions in the country.

“Our goal is to address the serious need for high-quality psychiatric treatment in the correctional setting and educate social systems outside of medicine and healthcare on psychiatric issues,” she says. “We collaborate with correctional institutions, forensic hospitals, and courts to consult on patients’ cases and train future psychiatry leaders to address the need.”

Biswas says aspects of the justice system can exacerbate psychiatric illnesses. Studies show delays in court procedures cause acute episodes of serious mental illness to become chronic or transform single bouts of inpatient treatment into a lifetime of revolving-door psychiatric admissions.3 Biswas says training psychiatrists to work with incarcerated patients is vital to protecting their rights to appropriate treatment.

“Many psychiatrists don’t feel comfortable testifying to patients’ illnesses at the time they were convicted of a crime,” she says. “But to improve legal and social justice for these vulnerable people, it’s crucial for doctors to learn to work in corrections and court environments.”

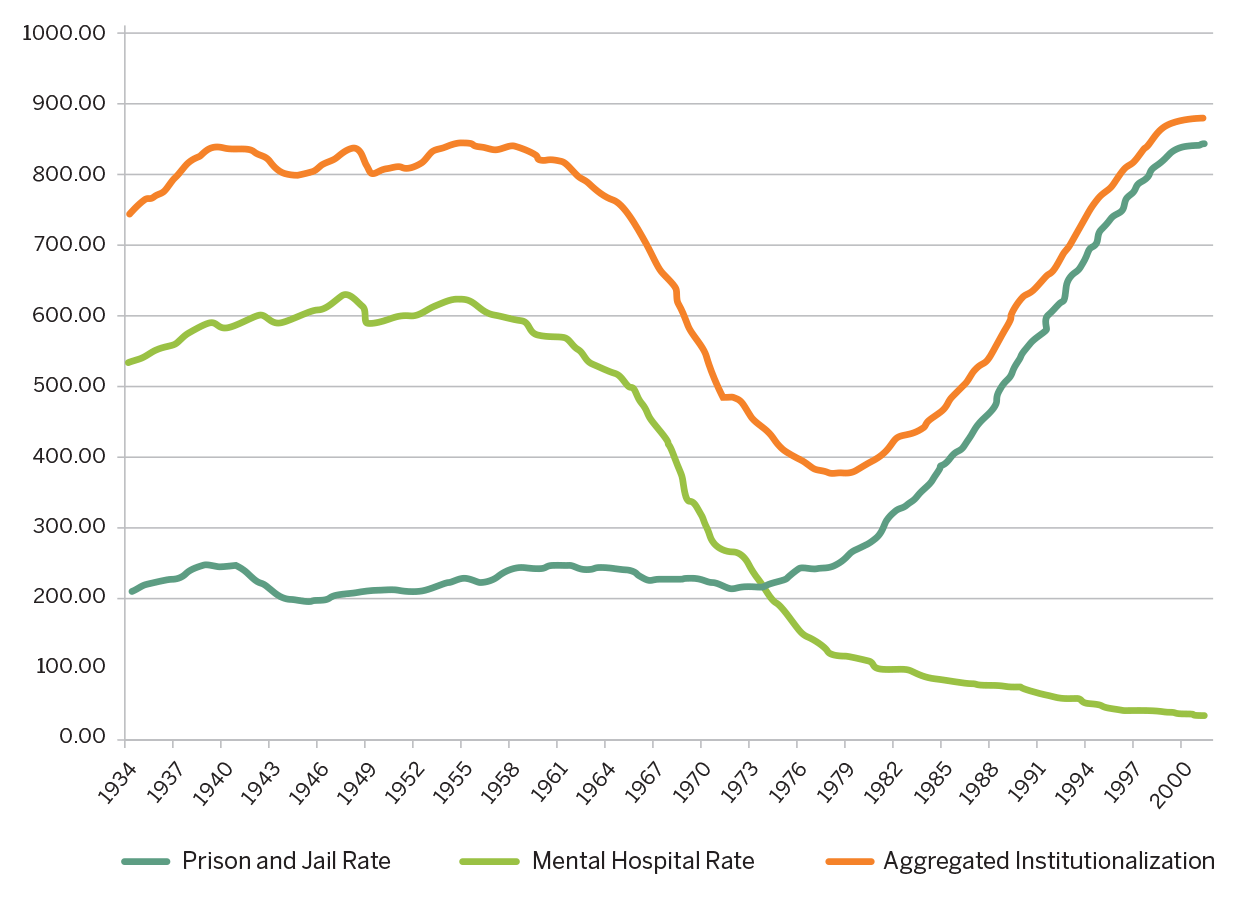

Rates of institutionalization, including jails in the United States

(per 100,000 adults), 1934–2001